The New Age Economy

Political Entropy. Digital Technologies and the Globalisation of Disorder. (Chapter 5)

Grigory Yavlinsky’s website, 18.12.2020

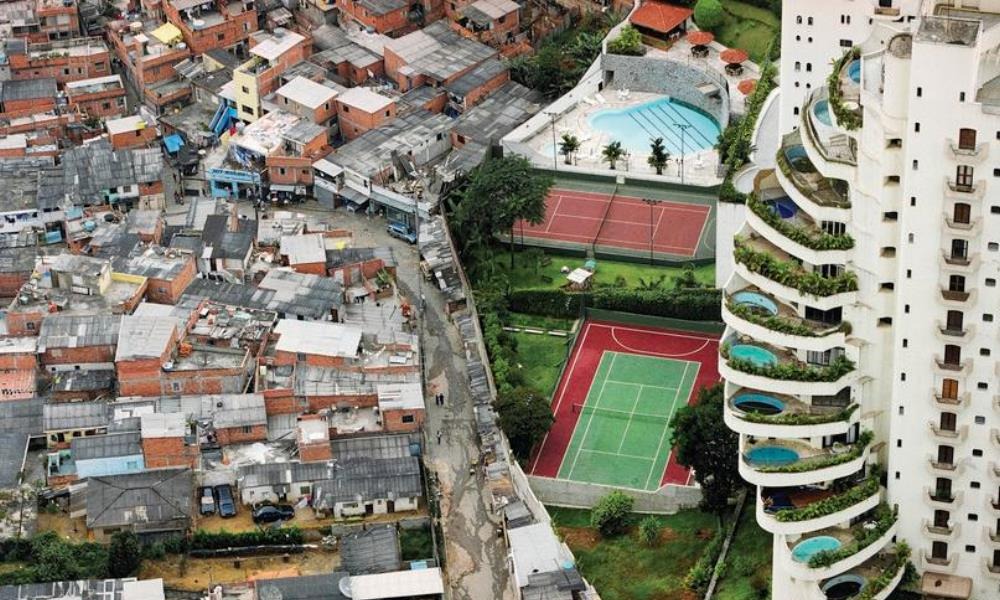

These days virtually all economic analysts concur that the pandemic and its consequences are exacerbating key negative trends in the global economy, such as the increasing gap between stock market indices and real economic processes, the rise in monopolies and growth of inequality. Arguably, the pandemic is consolidating the political power of oligarchic interests and postponing the opportunity to implement urgent economic reforms, creating an extremely conservative economic context (See «The pandemic and politics»).

When considering the link between the global financial and economic crisis of 2008-2009 and the current recession with long-term trends, fundamentally new factors were identified in the modern global economy1. For example, consolidation of the impact of historical and technological rents on structural changes in developed countries to the benefit of the new economy, and reinforcement of material inequality both within developed economies and also in the global economy, and also a change in the nature of the impact of scientific and technological progress on the economy. The thesis that public perceptions of benefits play a far bigger role in the economy than commonly believed has been confirmed.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES

Recent events have not only confirmed these observations, but have in many instances brought the consequences of these new phenomena in the economy to the foreground. Risks and fears related to the pandemic are expediting automation and use of robotics in many production facilities and services, notes the well-known American economist Joseph Stiglitz2. This also concerns sectors where nothing of the kind had happened in the past: education and health. The standard responses to such a challenge of accelerating professional retraining will be insufficient. Stiglitz holds: “There will need to be a comprehensive programme to reduce income inequality.” In his opinion, such a programme should proceed from recognition “that the competitive equilibrium model” that “has dominated economists’ thinking for more than a century” is already poorly suited to describe the modern economy with its monopoly controls on markets. Stiglitz notes: “Weakening constraints on corporate power; minimising the bargaining power of workers; and eroding rules governing the exploitation of consumers, borrowers, students, and workers have all worked together to create a poorer-performing economy marked by greater rent seeking and greater inequality.” He reminds us that the deterioration of the economy became apparent at the start of the pandemic when “American firms couldn’t even provide enough supplies of simple things like masks and gloves, let alone more complicated products like tests and ventilators.”

The situation in poorer countries is even worse, and affects directly both the American and the global economy. The economist is convinced: “The pandemic won’t be controlled until it is controlled everywhere, and the economic downturn won’t be tamed until there is a robust global recovery.” That is why it is in everyone’s interests to support countries falling behind in the fight against the pandemic, including the interests of rich countries.

To date, however, agreement has not even been reached on measures which had been implemented in the fight against the global financial crisis in 2009. This concerns the issue of special drawing rights by the IMF for USD 500 billion. Stiglitz believes that this has not happened due to resistance primarily from the USA and India. In addition, current “cheap money” will soon cause a wave of private and public debt crises and inevitable debt restructuring in some form or other.

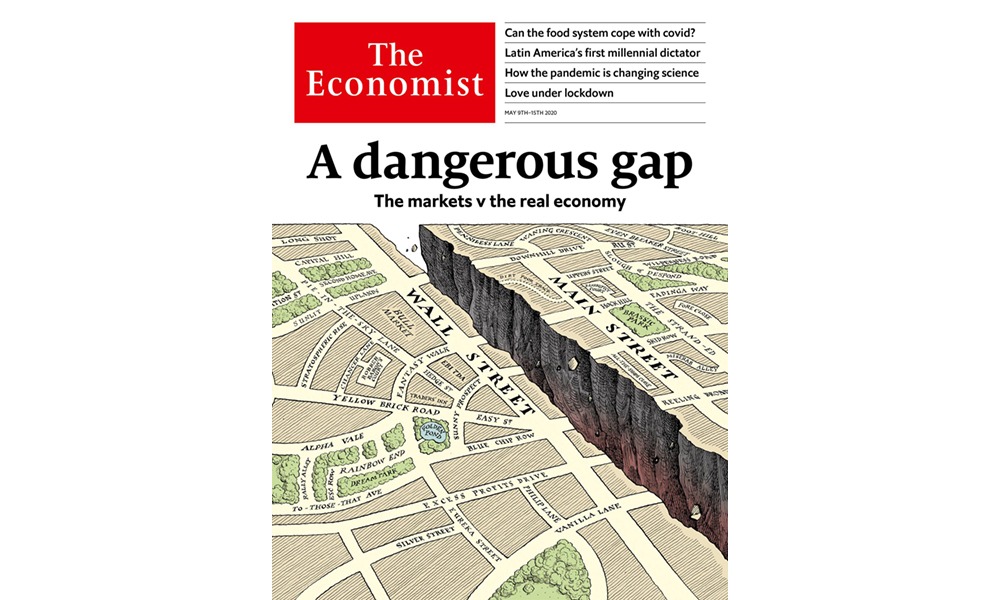

At the end of August the Chair of the Federal Reserve System Jeremy Powell declared an official change in the policy of the Federal Reserve System regarding inflation: instead of the objective of maintaining inflation at 2%, the so-called “targeting of inflation” has the goal of maintaining it on average at 2%. In other words, now a higher level of inflation is becoming in principle permissible, while the Federal Reserve System may hold the key rate at a level close to zero even if inflation rises above 2% for a “comparatively short” period of time. Against the backdrop of this news, the stock market shot up in delight. To all intents and purposes, this is a further development of the previous policy of pumping up the economy with “cheap money”. However, as Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist at banking institution and brokerage firm Charles Schwab, one of the large players on the stock market, explains, this money could not access the real economy, which was to a large extent in lockdown3. That is why all these funds went into the stock market and other exchanges, including trade in precious metals and junk bonds. The American financier Ray Dalio also writes about this trend, which appeared not only during the pandemic, but also during a decade of post-crisis “cheap money”4.

As a whole the stock market fully recovered after the March fall as if there had been no pandemic, and even went off the charts to pre-crisis levels (Dow Jones and S&P 500 have risen since March by 50%, while the NASDAQ-100, made up of the equity securities of digital and technology economy was up, 33%5).

However, the stock market is pulling away more and more from the economy, which is moving in the opposite direction. Real American GDP in the second quarter of 2020 contracted by 33%6. Recently four major retailers have filed for bankruptcy. At the same time, technology behemoths, such as Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Apple, Netflix, Facebook, did not suffer in the current situation, while some of them even benefited7. In particular, Amazon obtained one of the cheapest credit facilities in the entire history of the corporate securities market, while the net worth of its owner Jeff Bezos increased by USD 80 billion during the pandemic8.

The gap between stock market indices and the real economy is far from a paradox, writes Nobel Laureate and Professor of Economics Emeritus of Standard University Michael Spence9. In reality the stock market is reflecting “powerful underlying trends amplified by the “pandemic economy.” He notes: “Market valuations are increasingly based on intangible assets, not least the ownership and control of data …” According to one recent study of Standard & Poor’s 500, writes Spence: “stocks in companies with high levels of intangible capital per employee have recorded the biggest gains this year.” A detailed analysis of this trend in figures and graphs was published by Bloomberg Agency, under a typical heading which laid bare the ideological component of the new economy: “Stock Market Warns Workers That They’re the Problem for Business”10.

Spence also links this trend with the transition to digital technologies and partial closure of the most labour-intensive sectors, which has accelerated since the start of the pandemic (such as airline travel), where added value is generated thanks to labour and tangible capital. The Nobel laureate shares the opinion of Liz Ann Sonders that this is also facilitated by “cheap money”, reflecting government need to increase public debt in order to finance recovery programmes.

In general, it goes without saying that current developments in the global economic system are not only due to quarantines and lockdowns. A new era is coming which will clearly dovetail with the new economy. This is a wide-ranging topic. However, several concepts can be expressed briefly here.

The first concept is that the economy, as we all know, represents first and foremost the behaviour of economic agents. It is worth noting there that the psychology of economic agents is primary and unpredictable. The pretentious declarations of “true” economists that everything in the economy has been duly factored in and calculated, that they have “checked the harmony with algebra” and deduced clear formulae of the dependencies between all of them, are rarely confirmed in practice. Every time the reaction to economic variables may differ, and they cannot be predicted or calculated.

The second concept is that the world is entering a period of systemic change, including the economy (See «On the political systems of the New Age»). This is happening primarily because nobody knows where to invest and how exactly. Previously, this was more or less understandable, but isn’t now. And general phrases along the lines “the previous economy is being replaced by the new knowledge economy” fail to offer any clarity to the people who are required to adopt specific investment decisions.

In actual fact, this is not a “knowledge economy”, but instead a “post-knowledge economy” where every conceivable item of knowledge: а) May or may not be in demand; b) There are no mechanisms for consolidating specific knowledge as universally accepted (millions of “experts”, tens of thousands of theories and versions, thousands of communities — and they all say that they represent the supreme authority). This is particularly true in an environment where supply and demand depend not so much on technical decisions which make it possible to manufacture something that is clearly useful more rapidly, more cheaply and in large volumes (as was the case in the 19th century and throughout most of the 20th century), as on the manipulation of perceptions of our actual needs. In this scenario, needs simply cannot be calculated with a sufficient degree of probability. Naturally, the only exception would be instances when you yourself form the needs which are only being implemented for a select group, and definitely not for the masses.

That is why borrowing is now so cheap — however, nobody can take up the offer (if we rule out fraudsters).

This leads to a paradoxical situation: despite the abundance of “cheap money”, there is no quantitative growth, and resources are not growing more expensive. This can be observed most explicitly, for example, in Japan, but is not a purely Japanese phenomenon. In virtually all developed countries central banks are offering virtually free money in unprecedented proportions, while inflation remains at zero or at a very low level.

The fact is that money is not being handed out directly to consumers, but is being offered primarily as a loan to the financial sector. The funds accruing to consumers through the financing of budget deficits are to a large extent neutralised by the technology behemoths which are on the one hand digitising the services sector (including financial services), and thereby taking their rental income, and on the other hand absorbing additional liquidity through growth of their own capitalisation and the cryptocurrency product market.

Previously money assumed the role of the main limiting factor: if there were opportunities to take out big loans at low interest rates, then prudent companies would not find it hard to make profitable investments (despite the fact that mistakes would naturally happen, and the risks would be high and comparable with potential profits). Now, however, as a result of the expansion of information, communications and digital technologies, boundaries are determined by the ability to influence demand, form and attract this demand by persistently targeting the consciousness of consumers and managing them. And this is already a completely different economic system, a different system of business coordinates. And it goes without saying that there are different beneficiaries.

It would be wrong to say that there has been no discussion in Western political and economic research on the need to reform the existing system. The pandemic and the economic problems provoked or exacerbated by its impact, together with the threat of the authoritarian transformation of the political structure in the USA, are reviving this eternal discussion of ways to reform capitalism. Over the past few years the mainstream focus of the discussion was the microeconomics of big corporations. To a large extent, this was due to clear-cut or indirect acknowledgment that attempts by the authorities to materially reform capitalism through legislative institutions would effectively be blocked by big capital which wields control over these institutions through the financing system of election campaigns, the mass media and stock markets.

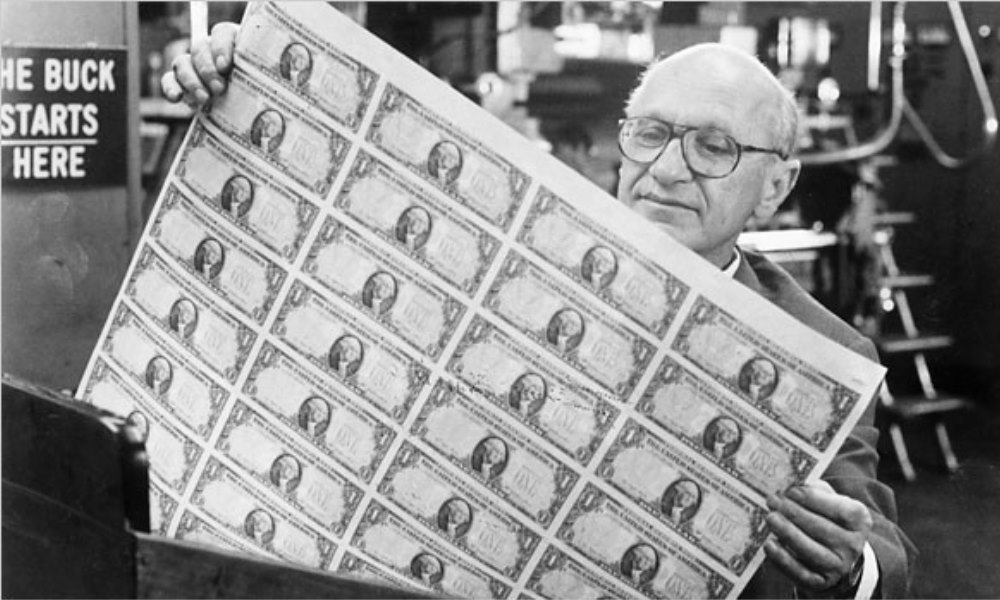

The main idea of the discussions during the past decade has been to change the goals of a company — to make the transition from maximising shareholder profits (an objective promoted by Milton Friedman11 and other representatives of the Chicago School of Economics) to achieving an optimal balance of the interests of different groups of people who affect the activities of a company directly or indirectly: shareholders, employees, suppliers, creditors, the consumers of their products and geographical neighbours. Harvard economist Dani Rodrik writes that the old microeconomic theory was based on assumptions regarding perfect competition on the market and the view that the availability of jobs is a purely economic factor12. In Rodrik’s opinion, both axioms became untenable after it became clear in economic and other social sciences that: 1) It is in principle impossible to dispose of infallible information when management and employees adopt economic decisions; 2) In the real economy “imperfect competition is the norm”; in other words, an unregulated market economy tends to end up with oligopolies or monopolies, consequently, companies enjoy power over employees that is at variance with the theory of a free market; 3) A job is not a purely economic category, but a “crucial part of an adult’s personal and social identity”, and the disappearance of jobs leads to destructive socio-political consequences for the middle class13.

As another Harvard scholar John Ruggie writes, the conceptual framework for this direction is the perception that through common efforts both from the outside and within it is possible to develop the social identity of a corporation, imbue major capitalists with specific behavioural norms, and educate them about their “core interests”, which coincide with the interests of employees and environmentalists, and thereby achieve the “self-regulation” of business14. Enthusiasm for these ideas is attributable to the fact that traditional forms of state and international regulation have fallen into decline and no longer work — due in no small part to the repudiation by democracy of political institutions which had ensured this external regulation (See «What should be done? Institutionalisation of values»).

However, recent research shows that the effectiveness of attempts at psycho-ideological transformation of the world of big capital and corporate management remains fairly low. For example, Harvard researchers Lucien Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita assert that the entire plan to reform corporate governance for its “socialisation” and market self-regulation is little more than a harmful illusion15. In the opinion of the researchers, this diverts the limited resources of a company and deflects discussion on the reforms of capitalism from the only effective area, namely the drafting of legislative and other political measures to curb capitalist excesses. At the same time, the authors acknowledge that movement along this path is extremely complicated, if not completely blocked16.

“There Is a Direct Line from Milton Friedmann to Trump’s Assault on Democracy” — this was the heading of a policy article that he published recently17. This direct line runs through a system where the “system for creating the rules of the game is corrupt”: as the advocates of market fundamentalism, representing the interests of big corporations, cannot impose their ideology on society in free elections, they do this through nationalism, racism and xenophobia18, which traditionally strikes a chord with the masses. What should be done? In Wolf’s opinion, corporations should be banned from participating in politics, inter alia, from financing election campaigns. He does not clarify who would be able to do this, given the degree of control of big business on politicians (something Wolf writes about).

Incidentally, Dani Rodrik might object here19 that the problem does not concern only financial control, but also the intellectual control of corporations, in other words, control over production processes and the dissemination of the information required to implement a competent economic policy, including business regulation. This intellectual control enables corporations to control the way problems may be articulated and filter any proposed solutions.

However, this is particularly interesting. The economic mainstream (with its beloved regressions and pretensions at profundity) has nothing to say about the appearance of some new global economic system. The most recent example is a global research report from Deutsche Bank20. The analytical department of Germany’s biggest financial institution is a completely representative forecasting structure with skilled personnel, graduates of the world’s best universities, and corresponding budgets. The research lists eight key “themes that will define the age of disorder”. Here you can find everything that you would expect to see: both global “concerns” about climate change, and “helicopter money”, with the “probability” of inflation, and new dynamism with the probability of inflation, and the impact of integration with the probability of fragmentation. And as a matter fact not a single word is written on what is happening in reality. Not a single word on why the previous levers of anti-cyclical regulation no longer work as they did in the past; why changes are being made to the structure and dynamics of demand and business capitalisation and what these changes are; how and why the nature and sources of economic and political power change, and who will now determine the political agenda.

It is true that the new economy will not expand instantaneously and the traditional real sector will recover partly after victory over the pandemic. However, the new global economic system, with the increasing concentration of information and digital assets at the very top of the economic pyramid will expand, and the disparity (and possibly, the conflict) between the two economies will become an intrinsic phenomenon in the medium and long term.

(1) Явлинский Г. А., «Рецессия капитализма — скрытые причины», М. : Изд. дом ВШЭ, 2014; Yavlinsky G. «Realeconomik: The Hidden Cause of the Great Recession ( And How to Avert the Next One)». New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011.

(2) Joseph Stiglitz, «Conquering the Great Divide», IMF Finance & Development, autumn 2020.

(3) See Why the stock market is divorced from the pain of a pandemic economy, ABC News, 15 August 2020.

(4) See Ray Dalio, «Why and How Capitalism Needs to Be Reformed», April 2019.

(5) See Stock Market Warns Workers That They’re the Problem for Business, Bloomberg, 25 August 2020.

(6) See US GDP contracted by a record-shattering 32.9% pace last quarter, ABC News, 30 July 2020.

(7) See Why the stock market is divorced from the pain of a pandemic economy, ABC News, 15 August 2020.

(8) See Amazon secures record low borrowing costs, Financial Times, 1 June 2020.

(9) See Michael Spence, Winners and Losers of the Pandemic Economy, Project Syndicate, August 2020.

(10) See Stock Market Warns Workers That They’re the Problem for Business, Bloomberg, 25 August 2020.

(11) See Milton Friedman, A Friedman doctrine. The Social Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, 1970.

(12) See Dani Rodrik, New Firms for a New Era, February 2020.

(13) See Dani Rodrik, New Firms for a New Era, February 2020.

(14) See John Ruggie, The Paradox of Corporate Globalization: Disembedding and Reembedding Governing Norms, August 2020.

(15) See Lucian A. Bebchuk, Roberto Tallarita, The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance, February 2020.

(16) See Lucian A. Bebchuk, Roberto Tallarita, The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance, February 2020.

(17) See Martin Wolf, There Is a Direct Line from Milton Friedman to Donald Trump’s Assault on Democracy, Promarket, October 2020.

(18) See Martin Wolf, There Is a Direct Line from Milton Friedman to Donald Trump’s Assault on Democracy, Promarket, October 2020.

(19) See Dani Rodrik, New Firms for a New Era, February 2020.

(20) See The Age of Disorder — the new era for economics, politics and our way of life, Deutsche Bank, 9 September 2020.

Posted: December 21st, 2020 under Economy, Elections, Foreign policy, Governance, History, Human Rights, Politics, Russia-Eu relations, Russia-US Relations, Без рубрики.