Russia-2022: Underlying Causes

Grigory Yavlinsky’s web-site, 2.06.2022

The most important specific of Russian national disasters is that they can all be attributed to the inadequate

capability documented in culture to respond adequately to the challenges of history.

Alexander Akhiezer1

In order to understand what has happened in Russia and before we even attempt to contemplate what comes next, we need to find an answer to the key question: why and how did we end up with a political system and state structure which has effectively organised the largest armed conflict between countries in Europe after World War II, with countless victims2, creating in the process a serious large-scale and direct threat to the future? Or to put it another way, why and how did a political system appear, which has resulted in the so-called “special military operation” against Ukraine on 24 February 2022?

If we fail to answer this question, we will be unable to extricate ourselves from the destructive path that Russia has already been taking for 30 years, while the developments today will also be repeated in future in the most savage forms.

We are witnessing and participating in monumental events. It goes without saying that they include moral, cultural and historical aspects. However, in this article I will focus on the underlying political causes of these developments.

REFORMS — CREATION OF THE SYSTEM

HYPERINFLATION AND CRIMINAL PRIVATISATION

The foundations of Russia’s current economic and political system were laid in the 1990s. The mistakes and crimes committed during the economic reforms of the first half of the 1990s created the framework and drivers of Putin’s present regime. This is when the underlying premises were created for the processes leading Russia to go to war today.

The headstrong, poorly prepared and ill-conceived signing of the Belovezh Accords in December 1991 signalled the radical disintegration of the Soviet-inspired system, the blunt and instantaneous rupture of all business ties which had evolved over decades3. Russian President Boris Yeltsin rejected the Programme for the Transition to a Market Economy and Economic Treaty with Former Republics of the USSR on the Creation of a Common Market4. Instead, adhering to the “Washington Consensus”5, the following key objectives were declared: “financial stabilisation”, liberalisation and privatisation in exchange for IMF loans. On 2 January 1992, Boris Yeltsin, acting as both President of the Russian Federation and Prime Minister, and his Deputy Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar, sought to launch the financial stabilisation of the country through so-called “price liberalisation”. In other words, price controls were lifted in a country which had no private businesses and where competition was conspicuous by its absence. In actual fact Soviet state monopolies were liberalised, leading to hyperinflation of 2,600% (in annual terms), and resulting in the de facto confiscation of all the savings of Russian citizens6.

The next step was criminal privatisation – the anonymous voucher scheme and so-called “loans for shares” auctions7. This was a fraudulent scheme implemented to transfer the largest and most important state property to a small circle of random individuals who had close ties to the powers that be8. As a result, we witnessed the merger of state power, property and business at all levels – from the Kremlin to rural administration9. And this how the foundations of the corporate oligarchic-mafia state were laid10. The most important institution of the inviolability of private property was not created in post-Soviet Russia, and the concept of private property was conditional from the outset – it was contingent, and is still dependent today, on the whims of the regime and may be redistributed at any moment11.

And this is how the system appeared – one where such democratic institutions as the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, a parliament elected by the people, the supremacy of law, freedom of speech and mass media not controlled by the authorities, posed an extremely serious threat, as they would have inevitably contested the legality of property seized to all intents and purposes through criminal actions. It goes without saying that a democratic structure and civil society were not developed in such an environment, but instead regressed12.

Today a number of events which are in actual fact of fundamental importance for Russia’s modern history, such as the shooting of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation in October 1993 or the presidential elections of 1996, are perceived as key events and are even referred to frequently as turning points in Russia’s history. In actual fact, however, these and other undoubtedly significant events of the past three decades were predetermined namely by the reforms implemented at the start of the 1990s. The model used to carry out the reforms in 1992 laid the groundwork for the crisis of October 1993 and its bloody resolution, as well as the creation and rushed adoption of the “super-presidential” Constitution in the same year. The entire progress of the 1996 presidential elections was predetermined by the distribution of property through the loans-for-shares auctions.

And this has nothing to do with fatalism or the inevitability of something that was predetermined. Reality is far more prosaic. After annihilating the savings of the population and cutting people off from participation in real privatisation (as it had been supplanted by the voucher swindle), the “reformers” knew all too well that personally they could no longer count on popular support. Moreover, the majority of Russian citizens began to represent a threat for the powers that be. In the eyes of most of the Russian population who had supported Yeltsin in 1990, democracy and the market would grant them access first and foremost to a qualitatively better life, instilled them with the hope that this would offer a way out from de facto gratuitous, and frequently inhuman exploitation and allowed them to believe that a state system based on respect for the individual was possible. In practice, however, the post-Soviet state offered Russians the old Bolshevik model: the democratic and market transformations turned out to be a goal which could only be achieved through tremendous sacrifice.

The position of the democratic intelligentsia in these years deserves a special mention here. At the end of 1991 – start of 1992 the intellectual leaders of the democratic movement, such as Yury Burtin, Yuri Afanasyev and Leonid Batkin, started engaging in profound criticism of Boris Yeltsin’s politics and reforms. However, their cogent and substantiated views on a number of important issues remained an act of individual self-expression. Most of the so-called “public opinion leaders” offered unconditional support for developments and rejected categorically the democratic opposition and any criticism whatsoever of Boris Yeltsin.

CERTAIN KEY EVENTS IN THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RUSSIAN AUTHORITARIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM

< navigation on the timeline from right-to-left using the arrows >

-

1991Headstrong signing of the Belovezh Accords; repudiation of the Treaty on an Economic Union with Former USSR Republics on the Creation of a Common Market and Banking Union; rejection of the Programme for the Transition to a Market Economy (“500 days”), prepared by Russian economists

-

1992Start of the implementation of the Washington Consensus reform plan as the criterion for the receipt of IMF loans; hyperinflation (2,600% per year) and confiscation of the population’s savings as a result of instantaneous price liberalisation against the backdrop of a state-based and hyper-monopoly economy; start of voucher privatisation

-

1993Refusal to discuss with society the disastrous progress with the reforms; constitutional coup and shooting of the White House; declaration on the “acceptance” of a heavy-handed authoritarian presidential Constitution

-

1994Start of the First Chechen War*

-

1995Loans-for-share auctions: fraudulent transfer of large state property to individuals close to the powers that be; an oligarchy starts to be formed; refusal to issue a state legal assessment of Bolshevism, Stalinism and the Soviet period**

* The decisions to start a full-scale war in Russia were adopted by a small group of people from President Boris Yeltsin’s entourage without the approval of the representative authorities. The plan for the invasion of Chechnya was only approved on 28 November 1994 by the Security Council. Admittedly, the meeting was attended by the chairmen of the chambers of the Federal Assembly — Vladimir Shumeiko and Ivan Rybkin. Both parliamentarians supported the invasion of Chechnya. However, neither the State Duma, nor the Federation Council had authorised Rybkin and Shumeiko to vote on their behalf. The Chechen war must be considered in conjunction with the events of autumn 1993 when the authorities talked about victory over the threat of the “red-brown revanche” and within a year launched the war in Soviet style with vast losses among both the military and civilians.

** G.A. Yavlinsky. A New Start. Second of July // Official website of politician and economist Grigory Yavlinsky. 31 August 2021. Access (checked on 4 April 2022).

*** The presidential elections were conducted in such a way that they undermined in Russia the nascent institute of elections, parliamentarianism and representative authority per se. The merger of state power and property was contingent on the immutability of the country’s leader. Even the possible questioning of the legality and legitimacy of the loans-for-shares auctions and any measures limiting the freedom of the ruling nomenklatura to dispose of the property that they obtained through criminal means were unacceptable for the new Russian elite. In the understanding of the leadership of the time and their retinue, the primary and overriding objective of the transitional period was to create through any means, inter alia, overtly fraudulent methods, a class of large private owners through the use of power to appropriate assets and property. The collective consciousness of these people, their ideas on what is admissible and inadmissible, possible and impossible, desirable and undesirable, etc. — all this objectively resulted in the appointment to the ultimate authority of an individual who would be able in their opinion to safeguard the interests of the beneficiaries of criminal privatisation and ensure the adoption of specific decisions which would create the criteria for the successful conversion of power into property. Everything aimed at guaranteeing honest market competition was sabotaged and vilified. This was a political choice, and as a result the country and its future lost outright. It is important to note here that as a rule the very same representatives of the post-Soviet intelligentsia lobbied in 1996 for Boris Yeltsin, in 2000 for Vladimir Putin and in 2021 for Smart Voting.

REFUSAL TO ASSESS STALINISM

The establishment of the current political system in Russia can also be attributed first and foremost to the failure of the post-Soviet authorities in the 1990s to issue a political and legal state assessment of the seizure of power in October 1917 as a state coup, Bolshevism as a political orientation, Stalinism as a terror-based system and the Soviet period as a whole13. A national discussion of the country’s history in the 20th century should have been organised, which would have resulted in a legal assessment of these events. However, the entire issue was reduced to a ruling of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation in 1992, which legalised the Communist Party of the Russian Federation14, and opinionated conversations on lustration. Soon the topic of assessing the past was closed. As a result the prospect of the possible restoration of a Neo-Stalinist regime under the virtual unlimited power of one man was retained15. The Chechen war started in 1994 was an imperial war. Everything that we see today in Ukraine – acts of violence and rape, lies, reliance on force and the disrespect of human life – both civilians and soldiers – already happened back then – 28 years ago in Chechnya.

On Joseph Stalin’s grave

beside the Kremlin wall, 2010s.

Ever since the start of the 2000s the regime has been artificially positioning post-Soviet Russia as the political heir simultaneously of both the Russian Empire and the USSR. As there had been no legal assessment of the Soviet period and there was no radical renewal of the bureaucracy, the Soviet-Bolshevik heritage was treated as a legitimate stage of Russian history which merited a successor. The realities of post-Communist Russia diverged abruptly from perceptions about them at the end of the 1980s – start of the 1990s when we dreamed about reforms and a new modern country.

The divergences turned out to be so material that the problem clearly no longer had to do with the disparity between idealistic expectations and actual practice. The vectors between anticipated changes and actual transformations diverged. In principle, the main hope of Russian society, which had appeared during perestroika – that we would witness a departure from the Bolshevik never-ending web of lies and acts of violence – turned out to be misplaced16.

APPEARANCE OF VLADIMIR PUTIN

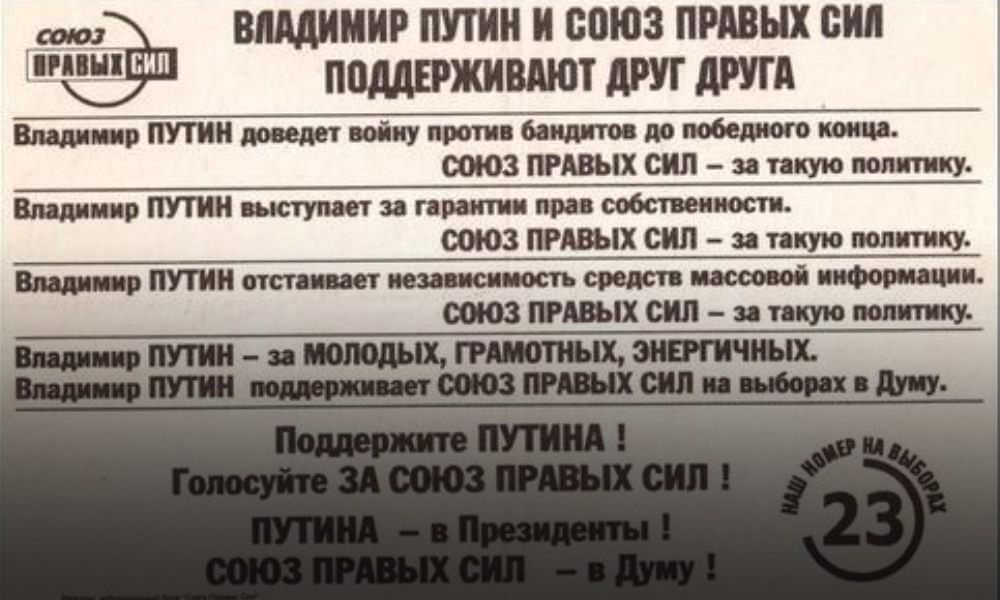

The appearance of Vladimir Putin as Russia’s authoritarian supreme ruler in 2000 was no accident or mistake17. This was a choice objectively dictated by the nature and logic of the economic and political system which had been created by then in the country. Someone was needed who would be expected to defend the results of criminal privatisation and the actual system. They selected a personality capable of literally adopting at a key moment the decision required by the system. Incidentally, it is specifically on the topic of war, on the widely reproduced meme “wipe them out in the outhouse” that the distillation of the popularity of the Prime Minister – heir of the Presidential seat – was built. It was already back then, in 1999-2000, that militarism was encouraged at all levels, backed by the approving yells of people of a so-called “liberal mien”18. Anatoly Chubais, one of the key architects of Russia’s oligarchic system, announced in November 1999 the “revival of the Russian army in Chechnya”, and termed appeals for an end to the war as a “stab in the back of the Russian army”19. And none of the so-called “hardcore democrats” — associates of Chubais from the party Union of Right Forces — objected20.

IDEOLOGY OF THE SYSTEM

Since the mid 2000s the system has been supplemented ideologically by the paradigm of Russia as a “separate civilisation” – in other words, a space representing something qualitatively different to anything existing in the rest of the world. Putin himself gradually became the key protagonist of this ideology, while simultaneously the product and builder of this system. Anyone whom he admits to his inner circle partly believes this to be true, and partly pretends to believe – they agree for the sake of self-preservation. It is not at all clear how Russia differs from the rest of the world as a separate civilisation21: only thing is clear here – such an idea in principle negates the need for Russia to select the European path and practically tries to make the way people live and organise their lives in the country regress one hundred years. Proceeding from this position, Putin believes that it is necessary once again, as was the case after World War II, to divide the world into spheres of influence, but this time – between Russia, China and the USA. In this system of coordinates, Ukraine is accorded in particular the role of a territory with limited sovereignty dependent on Russia.

It goes without saying that an imperial-nationalist vector has been more or less evident in foreign policy all these years. Today the Kremlin is once again trying to bring the post-Soviet space to heel. For the political system created in Russia, the emergence of independent Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia or Armenia as modern sovereign European states – with regular changes of leadership, real elections, an independent judiciary, the separation of powers, the inviolability of private property, and above all, the observance of human rights and freedoms – is in principle unacceptable.

All in all, the ideological platform without which it is highly likely that Putin’s “special operation” would have been impossible, was created in Russia almost three decades ago and stemmed from the specifics of the reforms of the 1990s.

The gravitation towards the ideas and practices of the far right has been a feature of post-Soviet Russia from the very beginning. The so-called “young reformers” seriously held in veneration Augusto Pinochet and studied intensely the experience of Chile’s dictator, without displaying the slightest discomfiture over the repressive nature of his regime22.

Two key factors – the hyperinflation of 1992, which was the underlying cause of the utter destitution of the population, and Yeltsin’s refusal to communicate with the people, resulting in the armed conflict with the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation in October 1993 – allowed forces disseminating far-right messages to take charge in the first elections to Russia’s new parliament (the State Duma) in 1993. The Liberal Democratic Party of Russia accumulated protest voters to a large extent and the subsequent development of events rapidly demonstrated the direct interest of the powers that be in a right-wing nationalist party. The link between the Kremlin and the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, which has always served as a reliable tool of the authorities on all key issues for its radical rhetoric, was clear. Since then extreme right-wing ideas have no longer elicited any rejection by a number of politically sensitive citizens.

The criminal loans-for-shares auctions commenced in 1995, which represented the wholesale deception and plunder of the state as an institute and the people (the privatisation of Norilsk Nickel is one striking example), contributed to the formation of the consciousness of a “resentful and dispossessed people”. And when Putin ended up in the Kremlin in 2000, it is not surprising that in a bid to distract the population and offset the failure of the reforms, as well as the profound deception and ignominy of the people, the regime selected an ideology, whose roots date back to chauvinist and imperial traditions. This corresponded to a significant extent to the role of contemporary Russia as the intrinsic successor of both the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire peddled by Putin.

It is notable that Putin and his entourage have cited the political theorist Ivan Ilyin on a regular basis ever since the mid 2000s.23 He has arguably assumed a special place in the design of contemporary Russian ideology. It is well known that Ilyin, when living as an émigré, was a vociferous opponent of Bolshevism and supporter of Mussolini, was until the early 1940s an admirer of German national socialism and sympathised with Franco and Salazar after the war. Ilyin believed in particular that the people should “love without reservation their national leader, believe him and believe in him …”, but at the same time should not participate in any way in the running of the state, as “the potency of the judgment of the remains pitiful.”24 This philosophical “lining” was much needed by Putin’s authoritarian “hierarchy”.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was also enthusiastic about Ilyin’s philosophy. Moreover, Putin’s rapprochement with Solzhenitsyn – with his ideas that “the entire South of today’s Ukrainian SSR (Novorossiya) and many parts of the Left Bank were never part of historical Ukraine” and the need “to protect the interests of those many millions who in actual fact don’t want to be separated from us”25 – after 24 February 2022 leave us in no doubt as to the sources of Russia’s contemporary political philosophy.

The year 2007, which ended with Putin’s Munich speech, started with the repeat publication in Rossiyskaya Gazeta of Aleksander Solzhenitsyn’s article “Reflections on the February Revolution.”26 The main conclusions from the article were drawn in pro-government and quasi-government mass media approximately as follows:

— “This was not so much a popular rebellion, as the pre-planned betrayal of the elite”;

— “Society’s victory in the one hundred year duel with the throne led to national disaster”;

— “The abdication of the Ruler is a betrayal of national interests”;

— “Every people is entitled to expect the use of force by its government – otherwise why would you need a government?”;

— The authorities must “be cold in their ruthlessness”;

— “Peacefulness is good for a Christian, but destructive for the ruler of a great power”;

— “The main danger for the state is not corruption, not crime and not bureaucratic arbitrariness, but rather a strong opposition.”

And this all turned out to be so modern and opportune! Here you have the concept of being surrounded by enemies and the “fifth column” and an immutable President, and a paranoid fear of the opposition27. Initially only the conclusion on the inadmissible weakness and indecisiveness of the absolute sovereign was important for state ideologues in the repeat publication of the long-held reflections of the Nobel prize winner, timed to coincide with the ninetieth anniversary of the February Revolution. Today this ideology has been invoked by the authoritarian regime in virtually all key areas to support the war.

I would like to point out in particular why the February Revolution which led to the fall of the Czarist reign was chosen specifically as the target of state propaganda. This choice was both momentous and significant: the Bolshevik coup in October 1917 and the disbanding of the All Russian Constituent Assembly have remained beyond criticism, whereas the Bolshevik-Stalinist totalitarian regime, which was not duly assessed after the collapse of the USSR, was already perceived in Putin’s system as the gold standard of a strong state and as a historical pillar of support in the regime’s revanchist aspirations. The works by Solzhenitsyn and Ilyin did not contain any positive assessments of Bolshevism. However, Putin had no need of their approval. Ideologues are not gurus for Putin, but instead the suppliers of material required to build constructs to substantiate his politics. Furthermore Putin himself picks from their utterances what he finds most apt. The very same Solzhenitsyn also wrote, for example: “The Ukrainian issue is one of the most dangerous issues for our future, it could deliver us a bloody blow <…> In any case, I know one thing for sure: should there be, heaven forbid, a Russian-Ukrainian war – I myself would play no role and forbid my sons from taking part”28.

Some ten years would be required before calls to bombard other countries, dismember or seize them, discussions on the country’s “special” path and “unique” mentality, “spiritual values” and on ending up in heaven in case of a nuclear war – were all to become commonplace in modern Russia.

The essence of a modern right-wing conservative and simultaneously Neo-Stalinist model is to reduce, simplify and seek to establish an authoritarian (totalitarian) dictatorship as the only option for Russian statehood. And this is exactly what is happening now. People are being persuaded that the Russian state (and in actual fact any “strong and competent” state) cannot take any other form, and that the only alternative is chaos (“you want to live like Kazakhstan?”29). Political entropy, the loss of the legal capacity of state institutions, the failings and “suspension” of democratic mechanisms are in actual fact key problems in the modern world. That is why Neo-Stalinism is not emerging out of the blue and does not look like a relic of the past in the current environment, out of place in a world of high technologies, social networks and a consumer society. The modern environment does not inhibit Neo-Stalinism at all: on the contrary it offers a convenient cover for its justification.

Putin’s speech in Sevastopol in November 2021 at the opening of a monument dedicated to the end of the Russian civil war is one such example30. Instead of public consciousness, honest historical reflection, an attempt to understand a tragedy which had happened more than one hundred years ago, Putin simply declared that everything was over, that the White and Red Armies had reconciled: “It goes without saying that most of them were Russian patriots and sincerely loved their country just like all the others who stayed behind to build a new country, and as they thought, a better life. “The others who stayed behind” were 56,000 to 120,000 White Russians who had remained in Crimea after the evacuation of Vrangel’s army and had been shot by the Bolsheviks in 1920-1921.

And this sums up Putin’s politics – “a single people – one leader – a common enemy”. The Russian officers shot and tortured by the Bolsheviks should not be considered enemies … as long as their followers acknowledge the state-forming role of Bolshevism. This is also Putin’s view of the succession of modern Russia – Stalin’s state anthem, the tricolour flag and the imperial coat of arms.

The fundamental and conscious anti-European course adopted by the Kremlin has gradually led Russia to the current misfortune and national disaster. On this path, the chances of the real modernisation of the state and the economy have shrunk to zero, as this political line has deliberately set our country against the world of the 21st century, discarded the experiences and achievements of the tragic 20th century and led Russia to adopt the same world view which gave rise to World War I and World War II.

“SOVEREIGN/MANAGED DEMOCRACY”

At the start of the 2000s the idiosyncratic concept of a “sovereign” or “managed” democracy appeared31. This concept was based on the thesis that most Russian citizens are not ready to fully participate in the management of the country through democratic procedures, consequently they need the patronage of an authoritarian, but preferably enlightened regime.32

An authoritarian system is being established in Russia, whose main traits are:

— the concentration of power in one centre: the President’s retinue, the gradual elimination of the independent role and influence of the State Duma, the Federation Council;

— the disbanding of federal mass media which are independent of the authorities, the targeted liquidation of public politics;

— the emasculation of democratic institutions, substitution of elections by a managed farce where the results are known in advance33;

— growth in the nationalistic power component in official ideology;

— growth in influence and expansion of the powers of the law enforcement agencies, transformation of the judiciary into a political punitive body to be used to prosecute the regime’s opponents.

Russian politics have started to associate the special military operation with its own idiosyncratic methods – indoctrination and active measures34. The important Bolshevik principle – any means are justified by the end goal – has again become the prevalent view. “It is highly likely that official politics is a special operation, where people say one thing, think something else, do a third thing, but want a fourth thing. Incidentally, as a result you end up with a fifth one” – this is a quote from the article “Time in Reverse”, published in February 2001.35

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

The merger of the oligarchic system and the resource-based economy rules out in principle the possibility of any modern technological development. This is precisely the reason why such projects as “Strategy 2020”, the proposals of experts from the Institute of Contemporary Development and other similar ambitious initiatives were not implemented36. And however much our “raw materials appendage” declares that it is an “energetic superpower”, as long as the system is not changed radically, neither 21st century high technologies, nor modern industrial production facilities will appear in the country. Against the backdrop of the economic and political system created in Russian over the past 30 years, any declarations about a “knowledge economy”, “human capital”, “technological leap”, and the like, are no more than idle talk37. Incidentally, it is vital that real modernisation be launched in the country as soon as possible to keep up with the times and the current march of history. Otherwise it will be too late – this chance will be lost forever.

Nevertheless even in this conditions there were some opportunities to implement an alternative programme throughout the 2000s and even in the 2010s, all the more so as the global state of the economy was propitious for our country. In the 2000s Russia had a unique chance to make the most of the extremely favourable state of global markets and invest the proceeds from the sale of oil and gas at sky-high prices in the diversification and development of the economy. It would have been possible to start implementing the “Land-Homes-Roads” programme38, provide radical support for small and medium businesses, create in the country state-of-the-art high tech sectors which would have generated income, regardless of oil and gas, and ultimately it would have been possible to build in the country a modern law-based state, with the separation of powers. However, none of this was done.

Naturally, the oligarchic system headed by Putin was structured intentionally to preserve what had already been achieved and exploit this fact for the purposes of blackmail and intimidation, and also for the consolidation of personal power.39 In these circumstances, the global state of the economy and persistently high hydrocarbon prices could not be used for the country’s benefit for the sake of its modernisation and became a disruptive factor. The Russian regime called to mind a drug addict, with the vein of one hand pumped with gas, and the vein of the other hand with oil, with the head addled with economic hallucinations40. In the absence of a new model, it relied on the old one which had not been adapted to the realities of the 21st century. And this is how Russia entered a stage of economic growth without development. And such economic growth without development, in other words, in the absence of the political, social and economic modernisation of the country and society, unsurprisingly had extremely dangerous consequences. The exaggerated beliefs of the “ruling elite” regarding their own abilities were formed and took root, while their unsubstantiated ambitions snowballed beyond all measure.

At the same time, however, it became clear that the absence of a major strategy was a problem that neither Putin, nor his entourage understand in principle. And this is the reason why the idea of moving forward, the topic of Russia’s future, has been absent from the Russian political agenda for almost two decades.

The cover of the “Land-Houses-Roads”

programme. 2011

However, there was a big strategy. This is the European way – objectively the only option for Russia. Everything else is the reproduction of Putin’s system and its course in some form or other along “the path that wasn’t there”41. It should be acknowledged here that a number of people shared this understanding in the country. However, the problem is that the nominal advocates of the European path of development did not consider their fellow citizens to be sufficiently European and were reluctant to talk to the country honestly and openly, recognising mistakes and failures, were unable to provide an assessment of the economic transformations of the 1990s. And this was precisely what was needed to change course. They should have discussed seriously and articulated positions on the key problems and the direction of the country’s life, such as, for example, the legitimacy of private property, the need to break up the oligarchic system; the merger of the state authorities and business42, a comprehensive assessment of Bolshevism and Stalinism, implementation of real economic reforms in the interests of the majority, ensure social justice and the equality of opportunities not through populist promises to dole out money or the “natural resource rent”, but instead through such programmes as “Land-Homes-Roads”43 or “Gas – in Every Home”44. However, these opportunities were used for different ends.

DECLARATION OF A NEW COLD WAR

In the absence of a strategy drawing on the realities of the 21st century, on the one hand, and Russian history and culture as an organic part of European history, on the other hand, a post-modernist trend was artificially created, which focused on the past: resentment, revenge, the restoration of “former glory”. In 2007, against the backdrop of sky-high oil prices, Putin announced a new cold war which had the goal of dividing the world into spheres of influence: let’s split up the world between Russia, China and the USA45. This was the “deliberate choice” of the Russian regime46. The break-up of the post-Soviet space, the events of 2013-204 in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea and the bloodletting in Donbass was the direct result of this choice47.

Did Russia have an opportunity to follow an alternative path in foreign policy? Strangely enough, it did, back in 2015 when Russia could have participated in the international coalition in the fight against international terrorism in Syria. In this case, however, the Kremlin would have been compelled to reject the anti-European course and try to rectify what it had done in Ukraine. Then the regime would have been able to come to its senses and avoid fatal mistakes48. However, Putin preferred an alliance with the Syrian dictator Assad, Iran and the terrorist organisation Hezbollah to any union with the West.

WAR IN SYRIA

In 2015 Russia became embroiled in the civil war in Syria. The Russian army practised air, land and sea strikes against Syrian cities and the civilian population. In rescuing Assad’s criminal regime, Russia’s leadership boasted that it had tested new types of weapons on people. Russian society, including individuals claiming to be liberal, virtually displayed no reactions whatsoever to the actions of the Russian army in Syria – this subject was not discussed by the opposition and was not a point in the political programmes of popular opposition leaders49. Today it is already clear that society’s indifference to Russia’s participation in the war in Syria also predetermined to a large extent Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine.

SOCIETY

DEFORMATION

The developments in Russia over approximately the past 25 years may be characterised not only as the refusal to build a modern society, a modern political system and a modern state, but also as conscious demodernisation50. Instead of a modern democracy, a superstructure was created gradually, but deliberately and consistently, in the form of a police state with a monopoly on information. In this environment any serious dialogue with the authorities on the real development path of the country became impossible.

As a result, we have witnessed the degeneration of society, one that is out of sync with the time, leading to a national catastrophe, and in the final analysis, possibly to the destruction of old Russia. This was also the main result of demodernisation. If an energetic society capable of moving forward and demanding serious institutional changes, as Russian society was at the end of the 1980s and start of the 1990s, is repressed by a straitjacket51 of lies and a police state in order to prevent its development, the process of new birth will still happen, but the offspring will be ugly. This was the case in the rule of Nikolas II of Russia: a regime totally cut off from society that refused to change its ways led to a situation when the desire of the Russian elite of the day to engineer the transformation of the Czarist regime into a constitutional monarchy in line with the times and thereby create the conditions for the further development of the country gave rise to the birth of a Bolshevik monster. One hundred years later a far more opportunistic, petty, vindictive, less educated and less erudite ruling elite, perceiving the development of society as a danger to their survival, has irrationally and absurdly pretended that there is no such thing as the development of society. This elite has once again straitjacketed society by imposing perverse restrictions and illegal bans, thereby programming the birth of the next socio-political monstrosity – the preponderance in politics of blatant illiterates, clowns, populists and radicals. And that is how we ended up where we are today.

Putin’s special action commenced on 24 February 2022 casts Russia back to the distant past. Furthermore, the issue is not only, strictly speaking, the actions adopted in respect of Ukraine, but also the lack of understanding as to what a state should be in the 21st century, what is meant by modern politics, and finally what Russia is. The imperialist military campaign unleashed by Russia is nothing other than the continuation of primitive Bolshevik politics.

THE PEOPLE

The Russian people have been deceived twice over the past one hundred years. The first time when they started believing after 1917 in socialism, only for everything to collapse after 70 years. The second time when people believed in 1991 that Russia might become a European country after the fall of communism. Here too, however, this was deception, triggering the most profound disillusionment.

The central feature of the system created in the 1990s was the need to safeguard from the people a regime that was seeking to stay in power eternally. The attitude of the country’s leadership to its citizens was expressed in cynicism – the majority was despised by a regime of the minority. The system required the depoliticisation of citizens: the resentful and dispossessed people had to be estranged from politics – not only from practical participation, but also from any political discourse as such. Initially, this was done allegedly to support patently unpopular reforms and was on this basis well received in alleged liberal circles. Subsequently, after the rout of the independent mass media and against the backdrop of the growth in oil prices, the depoliticisation of the population was required to create an authoritarian police system. In the final analysis, virtually all the mass media worked to achieve this objective and the required public agenda was formed: election rules were changed, political blocs were banned, the real elections of governors and de facto local government were cancelled, the practice of falsifying elections was expanded. The system’s monopoly of all the existing Russian television channels allowed propaganda to fill in virtually all the information space in the country. Furthermore, the key goal of the propaganda was to convince people that they did not actually influence anything and could not change anything. According to the implemented concept, the people would have zero influence on developments in their own country and the population would be entirely dependent on the authorities. This was coupled with the concept of hostile encirclement – both externally and internally in the form of “foreign agents” and the “fifth column”. People were instilled with the most distorted view of the outside world.

All this happened in an environment when the state resembled more and more a police state, when business was entirely dependent on the regime, and accordingly when the financing of institutes of civil society, political parties and trade unions, independent of the state, became impossible.

The crackdown coincided with an abrupt increase in oil prices when if not the majority, then a significant proportion of Russian citizens started enjoying comparative prosperity and certain benefits of civilisation. It looked as if the lack of democratic freedoms had no adverse impact on living standards, but vice-versa: freedoms disappeared – prosperity increased. Wealth appeared to be linked directly to the persona of the supreme ruler – the people by and large idolised and still idolise him, while “individuals with liberal views” blatantly despised the people for this fact. It should be acknowledged here that the feeling was mutual. A profound disillusion about the reforms, lack of political experience, the illusion of stability and ability to “live a private life, without interference, and go around honestly doing their business”, spurred them to be apolitical. The state supported this approach in every possible way and presented politically active citizens as raving madmen. The city’s “creative class” has never turned up for elections on a large scale, as it has not backed a single political party which advocates the interests of their social group. A small proportion of these people tried to protest publicly – admittedly, only in part, rarely and after the fact. Meanwhile, the significance of such an important action as elections has been reduced to zero, gradually, but persistently. And this is how the hope that each individual is important and may change something was destroyed definitively.

Naturally more than 20 years of intentional depoliticisation, targeted propaganda, aggravation of the atmosphere of fear, in the absence of alternative sources of information, led to a mass state of learned helplessness, in other words, a mindset and behaviour where the individual feels that he has no influence on anything other than some small part of his own daily life. Why did people suffer from learned helplessness? Because the regime deliberately made people end up in such a state. People lived in a similar situation in the USSR for decades, while the first years of perestroika and reforms instilled them with hope for change. However, a key domestic policy of Putin in the 2000s was to convince people of their utter political helplessness52.

Consequently, as a result of the reforms of the 1990s, against the backdrop of the utter indifference of the rest of the world, a system was formed in Russia where citizens could not influence in any way domestic and all the more so foreign policy. This even extended to the material conditions of their private lives. Today, when Russia finds itself in unprecedented isolation, such a position of the population is the trajectory of destruction53. “In the case of a people so committed and corrupted by the elite, one can only expect their final disintegration” – this is taken from a publication in 2011 “Lies and Legitimacy|.54

Of course, you can repeat as much as you want that, given Russia’s centuries-long history and the Soviet period, our people are not ready for democracy, and present examples and quotes to back this statement. There is no point contesting this fact – it is what it is. However, we must do what must be done in politics, honestly and correctly and let life put everything in perspective. However, if one is driven by greed, adheres to the rule that “the goal justifies the means”, commits base acts and patently implements the wrong steps, but which are personally beneficially to someone, then such a person should not subsequently blame the people for everything that has happened. This has nothing to do with the people: this is all about the individuals who consciously deceived the people, who were behind such actions – the ones who committed such actions and those who allowed them to be committed. Such figures were household names in our country and it would not be at all hard to name them.

THE INTELLIGENTSIA

The educated class, the post-Soviet intelligentsia, has played a special role in the creation and construction of the system. This concerns first and foremost individuals who believed themselves to be the elite, intellectuals, the intelligentsia in Russia – in general, anyone who is in actual fact reflected in the regime’s mirror.

Arguably, the most incontrovertible illustration of this role is provided by the active support of the post-Soviet intelligentsia for the erroneous reforms of the 1990s. These reforms could only be supported if one disregarded the needs of common people – through contempt for the majority of the population. To date a number of political scientists, economists and publicists justify and even extol the absurd reform plan of the 1990s55. As a rule, explaining the reasons for the failures of the reforms, and the consequent emergence of the current authoritarian mafia regime, they cite the fact that democracy in Russia “hadn’t taken hold” as the people were not ready. In their opinion, the reforms had been conducted in the only possible way, but the “people turned out to be unsuitable”56. In actual fact, the post-Soviet intelligentsia, the so-called elite of the country at the time when the regime disconnected itself from the people, opted to serve the powers that be and subsequently concentrated all their energies on relations with the regime and not the people.

Simultaneously overtly self-confident and at the same time incompetent, this stratum of Russian society was first of all divested of its political party (Union of Right Forces), cast out of the power structures, and then probably, undermined by their own inferiority complex, proactively participated in the removal of people from politics. For this purpose, incidentally, the mass media were used deliberately by the authorities (for example, Gazprom’s radio station Echo Moskvy57). In 2011 the people were told not to participate in the elections (“None of the Above”)58 or to vote “for anyone, but United Russia”59, while in 2021 they lobbied people, using “Smart Voting” to choose Putin’s loyal sycophants – the communists, supporters of the nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, supporters of the For Truth Party of nationalist Zakhar Prilepin, some alleged “new people”60. They tried ineffectually and through populism to supplant serious politics with activism61 and make the protest “non-political” – with white ribbons and Occupy Abay (“we don’t need politicians” – popular protest jamborees wearing white wigs along Moscow’s boulevards in 2012-2013; the refusal to support the democratic candidate for president in 2012 and 2018). And the main responsibility of the most proactive group of the post-Soviet intelligentsia – many years of the systematic smearing of the democratic opposition found guilty of criticising the absurd reforms of the 1990s and submitting coherent proposals on a professional economic alternative, refusing to support the actions and politics of Anatoly Chubais and other individuals from Yeltsin’s entourage and then Putin, and also rejecting the crackpot idea of a “liberal empire”62 and declaring unacceptable any alliance with Limonov’s National Bolsheviks63 , etc.

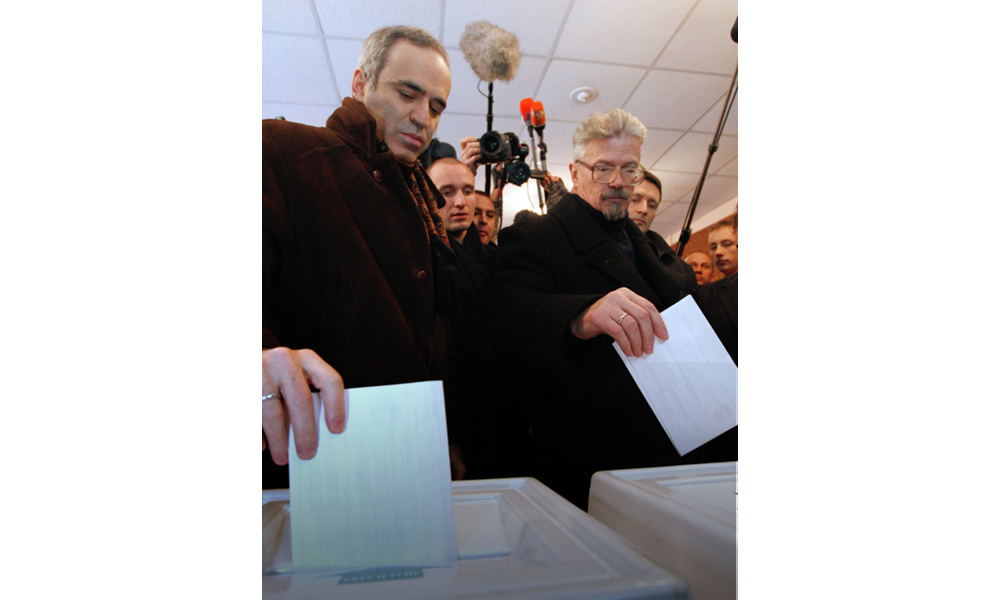

Garry Kasparov and Eduard Limonov are voting

during the parliament elections. 2.12.2007 //

Anton Denisov / RIA Novosti

CERTAIN EVENTS CHARACTERISING THE ROLE OF THE POST-SOVIET INTELLIGENTSIA

< navigation on the timeline from right-to-left using the arrows >

-

1992Unconditional support for Yeltsin’s reforms as the “only true course” and demand that the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation be “eliminated” as “red-brown interference” in the implementation of these reforms

-

1993Complete acceptance of Yeltsin’s side in the conflict with the Supreme Soviet which had escalated into a constitutional crisis and ended with bloodshed, as well as support for the new Constitution granting authoritarian presidential powers; lobbying in the State Duma elections for Gaidar’s Block “Russia’s Choice” and victory of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia.

-

1994Declaration by the State Duma of an amnesty for all participants in the October 1993 conflict in Moscow without an investigation of the reasons why this had happened and the Kremlin’s actions (the Yabloko fraction advocated the creation of a parliamentary commission to conduct an investigation) — the refusal to conduct a parliamentary investigation was welcomed by the post-Soviet intelligentsia

— 1995

Comprehensive support for the loans-for-shares auctions -

1996Total and unconditional support for Boris Yeltsin from the post-Soviet intelligentsia in the presidential elections — campaign “Vote or lose”

-

1999Declaration of Anatoly Chubais supported by the post-Soviet intelligentsia that “the Russian army is being revived in Chechnya”

Instead of all the above, it was vital to explain to the people and communicate via all available channels that participation in politics and in particular in elections (furthermore not participation mediated by algorithms, but instead direct voting for the candidate who is closest to you) is what is implied when you fight for your future, for the future of your children. For almost 30 years, ever since 1993, at least 11 times (eight times in State Duma elections and three times in presidential elections) there was a chance to turn politics in the right direction. That didn’t happen.

In general, it could be stated that the post-Soviet intelligentsia are responsible to a large extent for the current catastrophe. In addition to their support for the erroneous and criminal reforms of the 1990s and their irresponsible disregard of the democratic alternative – as stated above – the so-called Russian liberal elite has to answer for the second Chechen war and for bringing Putin to power in 2000, and for the enthusiastic acceptance of the annexation of Crimea in society – in other words, for all the key stages on the path to war with Ukraine.

The anti-democratic campaign in support of Boris Yeltsin in the 1996 presidential elections was to a large extent a watershed moment for the establishment of the system which led Russia to go to war in February 2022. At the time the proactive group of the post-Soviet intelligentsia voluntarily participated in lobbying on behalf of the current president, first and foremost, owing to their material dependence on the powers that be and the oligarchs close to the regime. However, the world outlook of leading representatives of the Russian intelligentsia, who still exerted significant influence on society in the 1990s, was also important. For it is specifically at this time, at the height of the extremely unsuccessful reforms, while fully aware and critically evaluating developments, that they still made a conscious choice in favour of the immutability of the regime. This position was not attributable to any fear of the Communists (whose ascent to power they simply used to intimidate others who doubted whether Yeltsin should be supported), but instead to a distrust of the country, the people, their attitude to the authoritative nomenklatura as the invariable minority that should hold onto power obtained once through the use of any means. This led to their backing for authoritarianism and justification of such authoritarianism, and as a result the genesis back in 1996 of the system which brought Putin to power.

At the same time, however, a significant proportion of the post-Soviet intelligentsia perceived a real democratic opposition – one that sought to preserve and strengthen the ties of democrats and most of the country’s population, to ensure the actual participation of the majority of the country’s citizens in politics (and not as mere toys to be manipulated or consumers of a political product, but instead as subjects of politics, as active players) – as interference in the reforms and the achievement of the goal before them: the creation. as they put it at the time, of a “new Russia”, and in actual fact a mafia-oligarchic system64.

In 1999 the fear of regime change reached a new qualitative level. Even people who had in 1994 collected signatures and spoken out against the first war in Chechnya now supported the second one without a twinge of conscience. These people became the allies of imperial revanchism. The very same Chubais, trying to come up with an ideology for the system that he had created with his comrades, talked about Russia as a “liberal empire”65. However, there can be only one kind of empire in Russia – nationalist. And vice-versa Russian nationalism may only be imperial. Any attempt to flirt with Russian nationalism is a movement towards imperial revanchism.

The course of the election campaign in the State Duma elections in 1999 (the imperial and militarist rhetoric of so-called liberals) and the regime’s policy in Chechnya (“wipe them out in the outhouses”) were already sufficient grounds for drawing a conclusion on the character of the new Russian administration which took up residence at the Kremlin at the start of 2000. Arguably, even those people who supported the KGB officer as presidential candidate, while continuing to claim to be democrats, had no illusions about Putin as a pupil of Anatoly Sobchak and the successor of the “founder of a free Russia” Yeltsin. Some of them made a paradoxical gamble on the preservation of democracy (as they understood it) through the use of anti-democratic methods. Others were knowingly ready to sacrifice democracy for the sake of preserving the property that they had obtained during the criminal privatisation.

This was followed by the dismantling of NTV as a private independent TV channel, carried out with the assistance of Gazprom and the participation of sophisticated “liberal” managers66. And the post-Soviet intelligentsia also swallowed this.

The absence of a long-term vision that I have noted as a systemic attribute of Putin’s state turned out be an intrinsic element of the Russian liberal opposition which spent years ineffectually on political activism67. The authoritarian regime should not have been countered simply by shouting phrases such as “down with Putin”, but instead with an image of the future. They should not have just joked about “identities”, but should instead have spoken seriously about values and goals.

To all intents and purposes, the protest “in-crowd” after the mass actions of 2011-2012, as a rule refused to focus on substantive issues68 and did not support an alternative to Putin either at the 2012 presidential elections, when he calmly returned to the presidential post, or in 2018 when the elections were transformed into a plebiscite on national support for Putin’s politics. Tellingly, many people from communities disgruntled with the regime treated frivolously even the revolutionary amendments to the 2020 Constitution – allegedly, the Constitution had not been working for a long time anyway.

Meanwhile, Putin’s system evolved, reinforcing the repressive component and nourishing imperial ambitions. However, instead of trying to counter this rapidly developing danger, the liberal “in-crowd” fed society with empty hopes that the system would collapse any day now, supporting the sensation that success was just around the corner.

Moreover, the failure to assess the importance of big ideas, clear value-based and ideological tenets, was accompanied by the promotion of ideological naked opportunism and all manner of “tactical” alliances with nationalists, National Bolsheviks and communists for the sake of the hypothetical expansion of the protest electorate. In the absence of a strategic vision, here too tactics supplanted strategy.

We have such a regime in Russia because it was allowed to take control by specific strata of Russian society purporting to be part of the opposition. Ever since 2007 and the conference of Eduard Limonov’s The Other Russia (Coalition), they have been preparing the country for a National Bolshevik revolution – and this was done, instead of trying to counter such a development69. For it was not the leader of the National Bolsheviks Limonov who provided the opposition with the agenda “grab and divide” (the counting of villas, yachts and flats as the main criticism of the regime). The nationalists did not strong arm the Moscow intelligentsia, demanding that they make xenophobia the banner of protest. This was done by the candidates for the role of leaders of the democratic opposition and their supporters who found nothing better to do than to piggyback on this left-wing nationalist trend and wait and see where the venture might end.

After their alliance with the National Bolsheviks, the same people placed their bets on the nationalist discourse on the individuals who had supported the war with Georgia proactively and aggressively (“strike Georgia’s joint staff with a missile”70) and advocated an anti-Georgian campaign in Russia and “Russian Marches”. At the same time, it should be understood here that nationalism is not simply a personality trait of Alexey Navalny, but rather an important component of his party line, a “point of principle” that he intended to use to become popular “with the people”. Betting on a populist politician advancing the cause of nationalism and the justification of such nationalism by the Russian intelligentsia, as well as the attempt to use the nationalist discourse against Putin, was an indefensible blunder. Russian nationalism is imperial in nature and cannot be anything else. The enemy in the nationalist and left-wing discourse inevitably becomes the West, and not the regime71.

Voting for communists based on the “Smart Voting” sales pitch was the final step in this erroneous line72. A public fight, not against the system, but only one of its elements – corruption – draws on the worst traits of human beings – envy, malice, xenophobia – and only fosters hatred. In Russia this is a major error.

Putin exploited the growth in nationalist and left-wing populist moods for his own purposes – for in actual fact nationalist, national imperialist and chauvinist ideas served as the basis of Putin’s politics towards Ukraine73. Everyone who was concerned that “Russians are Europe’s largest segregated people”74, who expressed their discontent over “others”, who sought enemies of the “Russian world” was offered one such enemy – Ukraine.

And if one cynically tries to convince the people, as the national populists and certain liberals did75, that a “war would cost too much” (for the state budget, the consumer’s pocket), frighten them with sanctions, explain that military confrontation was impossible as the army was unprepared, then war can never be averted. The true choice should not be between the fridge and the television, and not even between any conditional “victory” or “defeat”. This is an ideological choice – the issue of the value of a human life.

The liberal milieu and the intelligentsia failed to learn the lessons of the euphoria over Crimea and the war in Donbass, and a number of recognisable people from this environment participated in the campaign to support in the September 2021 elections Stalinists, nationalists, out-and-out supporters of war with Ukraine, seeking at any cost to reduce the percentage of voters for United Russia, assuming for no good reason that this would somehow weaken Putin. However, this campaign only ended up consolidating the system even more and facilitating the country’s transition down to the next level.

Ever since the end of the 1990s the Russian mass media commonly believed to be liberal or to represent the opposition (I am not even talking here about the overtly pro-regime media), increasingly became a tool in the fight against the democratic opposition. These publications defended the reforms of the 1990s and discredited alternative economic programmes, foisted on the audience the cult of the leader and populism and ignored democratic forces. At the same time, they inculcated a contemptuous attitude for the people who had not duly appreciated the achievements of the democratic reforms implemented by the tandem of Boris Yeltsin, Yegor Gaidar and Anatoly Chubais. This culminated in the lobbying for “Smart Voting”, in other words, for ardent proponents of the police state and war. The anti-war and anti-chauvinist democratic opposition not only miss out on any support: it was also trampled on. The idea of certain types of “new” communists and “good nationalists” was constantly hyped up and in the end, they hoovered up all the “protest” votes. The strong showing of the communists in the parliamentary elections in 2021 created the atmosphere and premises for closing Memorial and for the “special military operation” in Ukraine. “Smart Voting” on the instructions of the “leader”, which was declared a “protest” vote and became a mass phenomenon among people calling themselves liberals, in actual fact turned out to be a vote for the representatives of parties backing the regime which supported, support and will support the war. This was a clear illustration of an utter value-based failure and tactics devoid of any meaning, an eloquent example of the state of mind of the post-Soviet intelligentsia.

The West’s incompetence and the passion for advocacy journalism of European and American mass media claiming to understand political developments in Russia were the reasons for foreign support of the pro-Putin “Smart Voting”76 (even though the “Smart Voting” contributed to the war, Western politicians and the Western press to date have not conducted a review of this “political finding”). It has reached absurd lengths: Russian voters in London and Paris, after reading the Western press and the Russian internet, voted for a nationalist who had received a medal for the accession of Crimea and the war in Syria77. Now this “victor”, like so many others who received the backing of the liberal democratic and conservative, right-wing and left-wing press in the West, is on the sanctions list of the very same UK and France.

The deliberate Balkanisation and split of liberal democratic forces, degradation of political debate on the air waves of Echo Moskvy were beneficial, first and foremost, to the Russian regime, which had been using the radio station for almost three decades for the proactive weakening of the democratic opposition and, as a result, for support of the system and Putin’s regime.

Russian society will at some point understand that it is directly responsible for what happened on 24 February between Ukraine and Russia, for the political system that it created in Russia over the past 30 years. The Russian intelligentsia, drawing on the lessons of our country’s history, should be intransigent in its opposition to nationalism, populism, lies and the manipulation of people, should serve as a moral inhibitor, a safety lock. However, this public stratum has degenerated in post-Soviet Russia. It is not nationalism or left-wing populism per se, but rather the justification and even support of such ideas by those very people78 who should have stood up against nationalism, Bolshevism and revanchism on an ethical basis, which paved the way to the war.

THE MASS MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS

One should also highlight here separately the Russian journalists who decided, against the backdrop of an authoritarian regime, that they should continue to be “objective” and stay “above the fray”.

The rare, but until recently comparatively popular opposition mass media in the culture of protest, did over the years actually tell the people the truth about the crimes committed by the regime. The journalists of these publications, frequently risking their lives, published hard-hitting investigations of exceptional complexity, penetrating and extremely bold human rights materials. Without exaggerating, I would call a number of these individuals true heroes. At the same time, it is highly regrettable that the same publications and the same journalists failed to understand that there was a vital need to show intelligently and explain lucidly the political alternative: who could remedy the situation in the country and how this would be done.

And that is why the Russian police state believe that this press – as a rule, quite rightly – did not pose any danger for the regime, while at the same time adeptly exploiting it and the new specifics that have evolved in this post-modern environment, These specific aspects help to push people to a post-modernist world where everything is relative, where everything is called into question and subverted, where imitation replaces rational thinking and substance. And this leads to an increase in the spirt of activism: look, the questioning youth is moving, trying things out, making mistakes, but this is better than the “stagnant habits of liberal modernisers”. And this is where the lack of any ideological content or principles is a perfect fit, where politics resembles a game or sport, where it is OK to toy with Stalinists, nationalists and war mongers. This creates the illusion that all that is needed to help break the impasse is for some young people to search around and take stock of values.

As a result, the opposition mass media merely incited politically meaningless protests. Unable either to understand or perceive an alternative, they were naturally unable to support it. In their failure to explain who could change the system and situation in the country and how, such media incentivised some people to engage in a senseless rebellion, and prodded others to give in to profound apathy.

On 24 February 2022 we bore witness to a clean break with reality. This also happened, inter alia, as a result of the degradation of the Russian intelligentsia and a significant proportion of society. This is a break with time and history, with a real past, present and future, morphing as a logical result into the tragedy of the absurd, populating and even replacing life at all levels. Thousands of people are dying. We have brought the world right to the edge beyond which a major war beckons.

THE WEST

TOTAL DISREGARD

The West – the USA and the European Union – has made a sizable contribution to the creation, design and consolidation of the Russian oligarchic system and also played a significant role in pushing us to the current catastrophe.

For many years the West proactively supported Putin at a personal level: Tony Blair came to Russia to offer his support in the 2000 elections. George Bush Junior confessed after meeting Putin in 2001: “I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy. I was able to get a sense of his soul.” Putin has been praised by Berlusconi, Prodi, Sarcozy, Fillon, Kurz, Tsipras, Macron…79 The topic of the West’s influence on what happened to Russia is material and merits a detailed examination. In these notes, I will limit myself to some of the aspects which played a key role over the past 30 years in the development of the situation today.

CERTAIN ASPECTS OF THE WEST’S POLICIES WHICH SUPPORTED THE CREATION OF PUTIN’S SYSTEM DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY

< navigation on the timeline from right-to-left using the arrows >

-

1991-1992Interest of the American establishment not only in the democratisation and economic modernisation of the USSR, but also in the irreversible break-up of the Soviet Union; obstruction of the implementation of a national economic reform plan in Russia and the imposition in its place of the Washington Consensus that was entirely wrong in Russian conditions*, whose main results were hyperinflation and criminal privatisation

-

1993Unconditional support for President Boris Yeltsin from the West during the October constitutional coup and the military conflict with the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation; disregard of the Russian President’s refusal to enter into dialogue with Russian citizens and the use of brute force to solve the crisis

-

1994-1997Mass lending to Russia by the IMF during the war in the North Caucasus and widespread military crimes committed by the Russian army in Chechnya

-

1996Frank and unlimited support for Boris Yeltsin at the presidential elections, despite all the violations and falsifications and the start of the destruction of independent mass media in Russia

-

1999-2000Outright and unconditional support for Vladimir Putin in the presidential elections – the participation of the Prime Minister of Great Britain Tony Blair in Putin’s election campaign and blatant lobbying for him; the decimation of the civil population, Russian military actions and the carpet bombing of Chechnya in 1999-2000 did not stop the IMF’s lending to Russia (to all intents and purposes, US backing)

* See Information of the KGB of the USSR “On the Statements of the representative of the entourage of Mikhail Gorbachev dated 20 June 1991. See V. Stepankov, E. Liskov. Kremlin Conspiracy: Version of the Investigation // Ogonek, OGIZ, Moscow. 1992, page 55; V. Stepankov. State Committee on the State of Emergency. 72 Hours Which Shook the World // Мoscow. Vremya, 2011, page 55.

REJECTION OF NEW FORMATS

The deterioration in relations between Russia and the West over the past 15 years is not due to the much-hyped eastern expansion of NATO. The key problem was that ever since the start of the 1990s the West has not developed and has not proposed a new collective security system in line with the times, which would include Russia. This was essential and realistic. “The greatest failing of the West’s strategic choice after the end of the Cold War is, of course, the exclusion, isolation, and hostility of contemporary Russia”, noted William Hill in 2018, former counsellor of the US Embassy in Moscow in the 1980s80.

Were there any attempts to come to a mutual understanding? There were. However, they were not marked by conviction or persistence either on the part of Putin or that of Western partners. I refer here, for example, to the joint anti-missile defence system for Europe (Russia, the EU and US). In 2001 Putin discussed this issue at negotiations with NATO81, but no further development ensued. A Joint Declaration on New Strategic Relations between Russia and the United States was signed in Moscow in 200282, but not a single practical step was taken to implement it.

The lack of initiatives of Russian-European integration in security is attributable, first and foremost, to the lack of understanding of the significance of this process. When the European Union was created, its main strategy was to prevent a new war in Europe. However, as the years have passed, the European Union has been transformed into a bureaucratic structure which delineated its borders and started focusing on internal problems. The strategy of a Greater Europe and Russia’s European integration was not actually discussed seriously. As a result, instead of the strategically vital path of the rapprochement of Russia and Europe, an anti-European political agenda was formed in the Kremlin.

ENTROPY

On top of all this, developments today represent the collapse of fifteen years of politics pronounced by Putin in Munich. This represents de facto recognition of the collapse of fifteen years of policy in the Cold War that Putin declared to the West in 2007 in Munich – to all intents and purposes, this represents confirmation of this defeat. He failed to make Russia the leader in the opposition to the “unipolar world”, to attract to his side European politicians and citizens. “A Deliberate Choice?”83 boxed the regime, Putin and the country into a corner, while a reluctance to acknowledge his own errors and accept defeat in the new Cold War in the 21st century led to the decision implemented on 24 February 2002. However, the past one and a half decades became a time of loss and degradation, and this concerns not only relations with our country. Loathe to delve into developments in Russia, Western politicians and mass media even now continue to back the national imperialist wing of Russia’s opposition84, which has albeit acute differences with Putin, but these are only differences regarding the internal system. This is yet another painful manifestation of global political entropy85, attesting to political feeblemindedness. Donald Trump’s politics and the storm of the Washington Capitol on 6 January 2021 are due to the same range of symptoms.

Incidentally, for thirty years the West has also failed to notice in Ukraine the prospects for a Greater Europe. Even after the annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in the Donbass in 2014 nothing was created for Ukraine akin to the “Marshall Plan” – no timely and real steps were taken for Ukraine’s integration into the European Union. Putin’s “special operation” was required for the West to start to consider seriously the issue of Ukraine’s membership of the European Union.

As a whole, the West’s policy over the past three decades has been bereft of understanding and lacked a political strategy on the future that mankind could have sought to achieve. Indeed, Western elites have been handling current policies atrociously, there are more than enough examples: the flight from Afghanistan last summer, the dangerous and growing hostile confrontation in the United States between Republicans and Democrats, which holds out prospects of anything but normal pre-election clashes in American society, Britain’s Brexit and conflicts with the ruling parties in Poland and Hungary in the European Union86. It goes without saying that the economic and political model of the European Union is for Russia (and Ukraine) the absolute strategic benchmark. However, given the low quality of contemporary practical politics in the West and as a result its own problems, in the current situation we will have to rely only on ourselves and above all seek on our own a way to extricate ourselves from the catastrophe.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS

BACKBONE OF THE REGIME

On 1 July 2020 the Russian oligarchic system created during the reforms of the 1990s moved on to a qualitatively new stage of development: the immutability of Putin’s personal power was not simply enshrined in the country’s revised Constitution – this marked the official repudiation of the regime’s formal commitment to democratic legitimacy, of federalism, of progression from the Soviet past to a modern civilisation of the 21st century87. This signalled the definitive failure of post-Soviet modernisation. Democracy had been defeated, while the country’s modernisation never happened. And even though a number of people were not aware of what had happened at the time, and even now, the key result today is obvious – the lack of any prospects for virtually all the country’s citizens, the crushing of hopes and mounting resentment and disillusion. And it is always easier to channel all this multi-layered range of negative emotions against an external enemy.

And in this sense the war should not have come as a surprise. Indeed, Putin didn’t hide anything: he openly prepared the war, wrote and announced this fact vociferously. However, this did not elicit the adequate reaction – either within the country or beyond its borders. Putin’s anti-Ukrainian article published in summer 2021 was the most serious symptom and warning. However, the Americans were preoccupied with their rushed withdrawal from Afghanistan88, an election campaign started inside Russia, while the real danger of a war that had practically been declared did not become the main topic either for the mass media, politicians or public figures, however absurd that may seem right now89.

Today people in our country are exposed to the colossal influence of propaganda aimed explicitly at inciting hatred and support for the war. Add here the daily mounting fear of repressions. In such an environment individuals are ready to justify a great deal if only as a distraction from a perpetually negative mood. And there is more than enough negativity – war alone is hard to take, but there is also uncertainty and fear, which are caused in turn by the lack of reforms, social lifts, prospects and opportunities to influence developments, in other words, the lack of the institute of contemporary politics. All this has a stronger impact than other feelings, drowns out knowledge, experience, education and morals.

To put it another way, the main reason for the support of the war is the lack of freedom, the fact that people feel that they are prisoners, in a state of learned helplessness deliberately created by the regime. Russian citizens have ended up as the hostages of politicians who have an inverted, archaic consciousness, but the people are incapable of freeing themselves or changing anything at all. There are several reasons why this is the case: disillusion over the collapse of the reforms of the 1990s, the breakup of the USSR and loss of any future prospects, and at the same time a loss of understanding of the meaning of life. The formula of radical exclusion from politics – “You stay clear of politics, and in exchange we will feed and defend you” – yielded this result: instead of the construction of a European future, the national idea became confrontation with the West, a new world order, the messianic role of Russia and Putin. For it is a fact that people deprived of rights and freedoms, opportunities for fully-fledged participation in politics, self-realisation and self-respect, are ready to accept a totalitarian ideology. Furthermore, this ideology is becoming not only a tool used to manage the population, but is also at some point turning out to be an internal pivot for citizens. And as the absolute majority of people in Russia have to all intents and purposes already been shut out of real politics for a long time, the regime had no problem replacing the opportunities afforded to people in the modern free world by ideas out of step with time, corresponding to the century before last or the last century. All the more so as an authoritarian regime does not need creative and free people who want to replace it. The backbone of the regime has been provided by dependent, loyal and subordinate citizens.

PROTEST AND ACTIVISM

Nevertheless, there are millions of people in Russia who are against the war, millions who have not given into the propaganda. Then why has an anti-war protest failed to happen? Above all, this is due to the repressive laws. In addition, however, over the past few years, activist protest has been debased and defiled. Ten years were wasted on replacing politics with dilettante activism, emotional self-satisfaction90.