Political Entropy. Digital Technologies and the Globalisation of Disorder

Grigory Yavlinsky’s website, 1.12.2020

Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed

Everybody knows the war is over

Everybody knows the good guys lost

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

That’s how it goes

Everybody knows

Everybody knows that the boat is leaking

Everybody knows that the captain lied

Everybody got this broken feeling

Like their father or their dog just died …

And everybody knows

And everybody knows that the Plague is coming

Everybody knows that it’s moving fast …

Leonard Cohen, 1988

INTRODUCTION

The year 2020 is drawing to a close. One can only imagine what will come next. According to Deutsche Bank strategists, the era of globalisation, which has lasted for almost four decades, is coming to an end and will be replaced by the “age of disorder”1. Numerous unpredictable events and potential divergent paths lie ahead, and, as they say, no one knows which way we will go. However, even developments today are to a large extent indicative. For example, in public discourse pent-up demand for security is strengthening compared to the desire for freedom. From the state’s perspective, this translates into the tightening of controls, which have clearly been enjoying more public understanding, if not outright support. Tolerance of everyday restrictions and interference in private life has increased, inter alia, amongst the higher strata of society. This may also be true of political restrictions.

The value of the inviolability of private life is being degraded in line with the manipulation of individual interests and requirements which are being created artificially: this is a new trend which would appear to be here for the long haul. And all this is happening against a surge in populism: political systems appear unable to consolidate to block populist politicians, whereas the ability of the traditional elite to retain their role as a politically responsible class has weakened significantly.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES

The networking of communications, opportunities for allcomers to take centre stage, devaluation of the opinions of experts and specialists against the backdrop of a distorted, showtime flow of news and online anonymity — all these factors increase sharply the chances of an opportunist leader (See «Information ochlocracy»). The worldwide web, which has been voluntarily or forcibly turning people inside out, combined with populism in the form of political farce, has become a material factor in politics and public life. Information technologies free up and bring to the surface the darkest sides of human nature and sometimes not even populist, but instead absurd theories.

Take, for example, QAnon2 — a conspiracy movement based on the conviction that the leadership of the US Democratic Party and a number of American celebrities worship Satan and are involved in a vast international sex trafficking ring of young children. This movement appeared at the end of 2017 and since then has managed to attract tens of thousands of rank-and-file Americans and also celebrities. QAnon has been behind the transmission of a so-called “universal conspiracy theory”, which brings together virtually all well-known conspiracy theories, mystifications and the figures involved. In just three years a whole sub-culture has evolved around the ideas of “new conspiracy theorists”, with millions of screenings on YouTube, the sale of QAnon branded clothes and accessories. However, recently QAnon’s ideas have been openly expressed by politicians (including new US Congress members3): in social networks they write in earnest about the harm posed by vaccines and the implantation of microchips.

The influential power of QAnon’s theories on American society is demonstrated by poll results. For example, 44% of the electorate of the US Republican Party are convinced that Bill Gates wants to use a COVID-19 vaccine as a pretext for implanting chips in people and thereby monitoring them4. QAnon has rapidly broken free of the Internet into real life: the most dynamic and grassroots conspiracy movement has even assumed a life of its own without any creators, and is already having a global impact. Groups against Bill Gates on Facebook (“Collection Action Against Bill Gates”) have attracted hundreds of thousands of participants from all over the world. In May 2020, real mass protests swept through New York and London over the “attempts” of Microsoft’s founder to “implant chips in people and commit world genocide through coronavirus inoculations”. In spring 2020 vandals in Great Britain attacked dozens of telecommunications towers that followers of conspiracy theorists cite as one of the reasons for the spread of COVID-195.

In the USA over 60 million people are convinced6 that the results of the most recent presidential elections may well have been falsified. This means that in his four years as President Donald Trump managed to achieve something that all the opponents and enemies of the United States had failed to do during the past two hundred years – starting with the Apache and ending with the Al-Qaeda terrorists. The long-abiding belief of the American people in elections has been undermined. And that is not all. Such key democratic institutions as the judiciary and the press have been jeopardised as well.

On the other hand, it is specifically during Trump’s term as US President that the mass movement Black Lives Matter was formed and related widespread race riots erupted. And today it is highly unlikely that the genie can simply be put back in the bottle. The radical ideas of Black Lives Matter, which are extremely similar to the class divide at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries, will trigger an even greater rupture in American society.

The lack of trust in key institutions, the hatred of elites and their weakness, the increasing stratification of society and inequality of opportunity, the emergence of class-like mass protest movements – these are all manifestations of an impending crisis. And it goes without saying that this has nothing to do with the specifics of the recent presidential elections in the USA when significant issues were side-lined – not simply treated as secondary issues, but instead put on the back burner, as the media constantly chewed over the scandalous details of the private lives of the candidates. The crisis is marked by the strengthening of the positions of a totalitarian consciousness, counterbalanced by attempts at rationalisation.

Totalitarian consciousness (not necessarily in extreme sectarian forms) is inclined to perceive any political conflict not as a competition between alternatives, but rather as a confrontation between the Truth and Falsehood. And such a vision proved very popular at the most recent US presidential elections. Naturally this is not a new phenomenon for Americans. However, whereas in the past foreign dictators would as a rule personify falsehood and lies, today such evil is already permeating the country. The damage caused over the past few years to American institutions is not that notable at present, but will definitely make itself felt over time.

How do you overcome this crisis and rectify all the damage? We are not talking here about merely cleaning up the house after some seedy con artist threw his weight around. In actual fact, the aspirations to turn back the clock and return to some past order, to simply sit out the storm that has enveloped the whole world – this brings us very close to the Trumpian “Great Again” overtones and is far removed from reality. The political crisis in the USA, as incidentally is the case everywhere in the world, cannot be resolved just by Joe Biden’s victory. It is clear that fundamentally new solutions are needed. The first step we need to take is specifically to realise how and why the world has changed over the past three decades.

Meanwhile digital platforms are being transformed at breakneck speed by populists into breeding grounds of far-right ideas and practices. It is well known that populism can easily be converted initially into nationalism and then into fascism. Populist ideas underpin authoritarian corporate states, stand behind monopolisation in the economy and politics, engender aspersions that it is a mission against the outside world. For it is populism that seeks to convert such phenomena in domestic politics as the unity of the people and the powers-that-be, the fight against external threats as the meaning of the state, the fight against traitors of the country and conspiracies as the basis of security, into defining issues (See «On the political systems of the New Age»).

The impending era also imposes another acute challenge — the new economy which persistently requires re-evaluation at an institutional level of such key concepts as monopoly, ownership and competition (See «The New Age economy»).

On the whole, from the outside today everything in life looks the same as in the past. However, a vast number of people don’t understand what is happening, feel lost and don’t know what to do. This provides the authorities with an opportunity to convince people that there is no alternative, that a decrease in the degree of freedom of choice is wholly beneficial. It is telling that the slogan “TINA: There is no alternative” has been become extremely popular recently in the West — it was actively used at one point in the past by Margaret Thatcher, who was British Prime Minister at the time.

And in actual fact mankind is entering a new era where it has effectively been deprived of any alternative. In Russia, a highly authoritative corporate state with an unchanging leadership has been established definitively. In the USA two candidates aged 74 and 77 competed for the presidency, and fought so hard that after the elections the country is virtually bordering on civil war. People in Europe are increasingly afraid of refugees from third countries, and populists, if not nationalists, are coming to power one after the other. Meanwhile Communist China is strengthening its industrial and technological expansion.

A series of articles under the general heading “Political entropy. Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder” consider the underlying processes triggering the crisis phenomena in global politics and forming the new age economy. In addition, the publications refer to serious changes in society accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic from the context of the impact of the fourth industrial revolution, above all, information and communications technologies, on politics and individual lives. In the final analysis, the key issue of our age is whether mankind is capable of determining its future. The goal of this series of publications is to draw attention to the specifics of the new era and to try to map the path ahead.

April — November 2020

The author would like to take this opportunity to express his heartfelt thanks to colleagues who were involved in discussions of the articles: V.G. Shvydko, A.V.Kosmynin, G.A. Melamedov and D. Y. Glinsky

As a series of events sent shockwaves globally, a large-scale process proceeded in the background imperceptibly, with the creation of new forms and methods to manage social phenomena, to all intents and purposes representing the birth of a new type of political system.

It has been clear to everyone that political systems in Western countries have started showing signs of strain during the past decades — and have been malfunctioning. Externally, this was manifested in the inability of political systems to effectively counter manipulation by forces and factional groups extraneous to the previous balance of interests.

It goes without saying that fringe politicians with authoritarian views have always existed. However, now they have started assuming far more substantial roles in their own countries and have already started forming coalitions between each other. The key factor uniting these politicians is a rejection of the significance of and even need for the European-style political system that appeared after World War II, and repeated attempts to present this system as “wrong”, unfair and unviable. There have been more than enough examples: Donald Trump in the USA, Boris Johnson in Great Britain, Vladimir Putin in Russia, Recep Erdogan in Turkey, Andrzej Duda in Poland, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

It does not always involve outright rejection — frequently these ideas are veiled under calls for “reform” of the political system. In most cases, this is manifested in the form of populism — calls for the restoration of the primacy of the interests of the people (for example, “Brexit”), juxtaposed against a corrupt and egoistical “elite”, and promises to make this happen if elected. At the same time, in most instances this does not concern the entire population, but instead the so—called “real” people (“true”, “with core beliefs”), who are proponents of the “right” traditional values. Moreover, such people oppose not only the elite, but also other “foreign” elements and values. It is implied that they are not satisfying the demands of the whole population, where you will find diverse minorities and special groups, but only those of the “indigenous” population defining state identity.

It is notable that in such cases as a rule the changes imply not so much the establishment of some new, more progressive and just order as the restoration of some old order that had allegedly been lost for good. In this sense the new populism (incidentally like its forerunner) addresses the past, some more natural, but lost order which had allegedly ensured justice and greatness at some point in time. And this represents the core of the explicit anti-globalism of the new populism, its focus on national historical values, calls for the restoration of former glories, which are as a rule dubious from the perspective of the values of humanism, and to a large extent mythical (“again policy”)1.

However, populism (based on the above understanding) is not the only phenomenon reflected in the increasing rejection in Western countries of the values of the political structure of society which gained a foothold after World War II in developed parts of the world. Another key symptom of today’s political about-turn has been the negation of the values of private life, disregard for privacy and autonomy as an indelible right (and to a certain extent attribute) of the individual.

As such, it is namely the separation of private life from public life, independence from public dictates and control which represented the most important element of the concept of political and social progress throughout the 20th century. However, in the past decade the freedom of private life as a value has become a target of contempt, if not actual repudiation. Against the backdrop of the unprecedented and rapid expansion of opportunities for official and unofficial structures (and also the specific parties standing behind them) to control the actions and thoughts of individuals, resistance to such processes turned out to be surprisingly weak and impermanent. Most of the population was subconsciously already prepared for an intensification of controls — both physical, and also cultural and spiritual — in exchange for home comforts and social prestige, which is frequently illusory or confined to a narrow group. Moreover, opportunities for the integration of the spiritual lives of individuals on large-scale single platforms, which are comparatively susceptible to control and external influences, began to be perceived as a public achievement and form of progress.

Finally, another key aspect of Western political structure of the second half of the 20th century, which has been significantly weakened over the past decade, was the hierarchical nature of the organisational system for running society. The “networking” of society2 so typical of today, accompanied by a wide distribution of forms of influence, and accordingly a decrease in individual responsibility, has ambivalent consequences. On the one hand, traditional leaders who have aspired to leading roles in a vertically organised society lose the opportunity to influence public moods and political decisions to the extent that they could in the past. On the other hand, utterly random people are promoted to the role of leaders (often impromptu individuals or so-called “men of the people”), who just happened to be at the crossroads of different networking platforms.

As a result, there has been an abrupt increase in the number of random outcomes in political systems unrelated to the actual balance of interests of public groups. More and more opportunities appear for fringe players and irrational actions, for virtually inexplicable and at times strange political decisions attracting unexpected support and a chance at implementation. Presented by enthusiasts as a tool democratising governance, in reality, “networking” generates chaos and irrationality and fosters growth in random movements frequently initiated by the beneficiaries of such destabilisation, whose goals are diametrically opposed to public interest.

Why have we witnessed all these phenomena over the past decades? There is no unambiguous response to this question if only because too little time has elapsed to draw final conclusions both on the substance of this process and also on its causes. Nevertheless, some explanations can be found, which are worthy of consideration.

All these developments can be attributed to processes frequently called the fourth industrial revolution, specifically the impact of new generation information and communications technologies on the social and political sector related to the expansion of the internet, the opportunity to collect and process large arrays of data, and use elements of artificial intelligence. These technologies, adapted for use in mass communications, triggered the dilution of the foundations of the “classical” Western model of political organisation of society (See «Information ochlocracy»).

How?

Firstly, information and communications technologies made it possible to “network” social communications in society: without the internet and its potential, there would be no social networks where anyone can announce their political ambitions and address a mass audience without any public mandate to engage in a political career. For example, today an unknown young ambitious activist can access an audience running into millions: if in the right place at the right time, such an individual just needs to make a little effort and be lucky. These days there is no need to spend countless years climbing the rungs of a party ladder or embark on a painstaking administrative career, meticulously establishing vertical and horizontal ties, and proving leadership skills and business qualities. All an individual needs to do is simply attract the attention of a group of active users through a striking image — and the viral dissemination of content will transform any such random individual into a political figure and a public opinion leader. Previous filters operating on the basis of financial control and selection criteria no longer work.

Secondly, information and communications technologies eliminated the tried-and-tested age-old system for influencing the public mood of using informal leaders of local and professional communities — or to put it more simply, authoritative figures for different population groups. Online any informal leadership is diluted and gives way to the political and behavioural patterns of a loosely organised crowd. Meanwhile, everybody knows that a crowd does not tend to a react in an orderly manner to significant political events and is unable to support rationally planned protracted campaigns, but is by contrast a pushover when it comes to incidental issues. Naturally, such communities can also be successful targeted. However, the tools available to achieve such an impact have little to do with the logic and structure of a party representative system.

Thirdly, another attribute of the new forms of communication concerns the disappearance of any hierarchy regarding the significance of events. I am not talking about the so-called gutter-like journalism spewed out for the mainstream audience, but rather the fact that this agenda is incapable of ranking events by their degree of importance. Data flows are being transformed into anarchic batches of messages/reporting and interpretations of such reports where news of utter irrelevance from a social perspective is mixed with events that could have significant implications for millions of people. Both online, and also offline in the traditional mass media in new information formats (for example, socio-political talk shows or continuous “news” broadcasting on TV channels), political events are presented in a cynical diverting or overtly perverse form — on the same level as standard entertainment; propaganda is jumbled up with advertising that debases its own content; gimmicks deployed to attract the attention of the average consumer (increase ratings, offline and online traffic) openly take precedence over the substance of the information. As a result, comparatively streamlined and ranked knowledge on the life of society is replaced by an endless entertainment spool of words and images, interfering with real news and at times rendering any understanding of developments and their potential consequences impossible.

Fourthly, the virtualisation of social interaction releases the negative energy previously suppressed to a significant extent by physical personal contacts between different sections of society. It goes without saying that such phenomena as “hate speech”, “trolling” and others are nothing new. However, they are becoming far more common and hostile in the absence of direct physical interaction. For the time being the political consequences of this phenomenon are not entirely clear, but there is no doubt that this will undermine the effectiveness of tools used in traditional party and parliamentary systems. The radicalisation of political conflicts, perception of such conflicts as an uncompromising fight between “us” and “them”, incompatible with the substance and intended purpose of such systems, render these institutions dysfunctional and meaningless.

Incidentally, it could be assumed that the development of these technologies merely act as a trigger, while the outcome of any scenario is determined by the lag of human consciousness behind the achievements of the fourth industrial revolution.

For example, this is expressed in the generation gap — when the older generation is incapable of fully recognising and accepting a world that is changing so rapidly, while the young take everything for granted. However, instead of looking for answers to the questions “What is the point?”, “Why?, “Is this actually needed?” and “Could things be done differently?”, the new generation is preoccupied on how best to leverage the “rules of the game” which are already equated to the insurmountable laws of nature.

People believe that algorithms are replacing institutions and bringing happiness to mankind; that there will be no need for politicians, scientists, doctors, teachers, institutions and systems; that their places will be taken by technologies which will be available to everyone: given that everyone has a gadget that can be used to download apps, this means everyone can use the algorithm, and that everyone in future will be able to print whatever they want on a ЗD printer…

In any case, all these factors demonstrate that the crisis of party and parliamentary systems in leading countries in the West is not some accidental short-term aberration. It is the natural consequence of the expansion of new information and communications technologies in the political sector, and accordingly represents a serious challenge for the future. The Western political system was also simultaneously a representation system of the boundaries of what is permissible in politics, in other words more or less sustainable boundaries that an individual could not transgress without being cast out of the system.

These boundaries have expanded significantly with the emergence of the current generation of populist politicians. At the same time, however, today the system is not discarding the people who have been expanding them. And most importantly, nobody knows how widely the boundaries can be expanded right now. Can any information be disregarded just because it has been called fake? Can a law be declared wrong/unjust and not be implemented? Can we simply refuse to recognise the results of elections? Can rules actually be changed unilaterally, with total disregard for previously established procedures?

For the time being nobody knows the answers to these questions. However, if all the above is possible, then this will already be a different system. Fundamentally different, even though formally all previous institutions will be retained: parliament, the judiciary, etc.

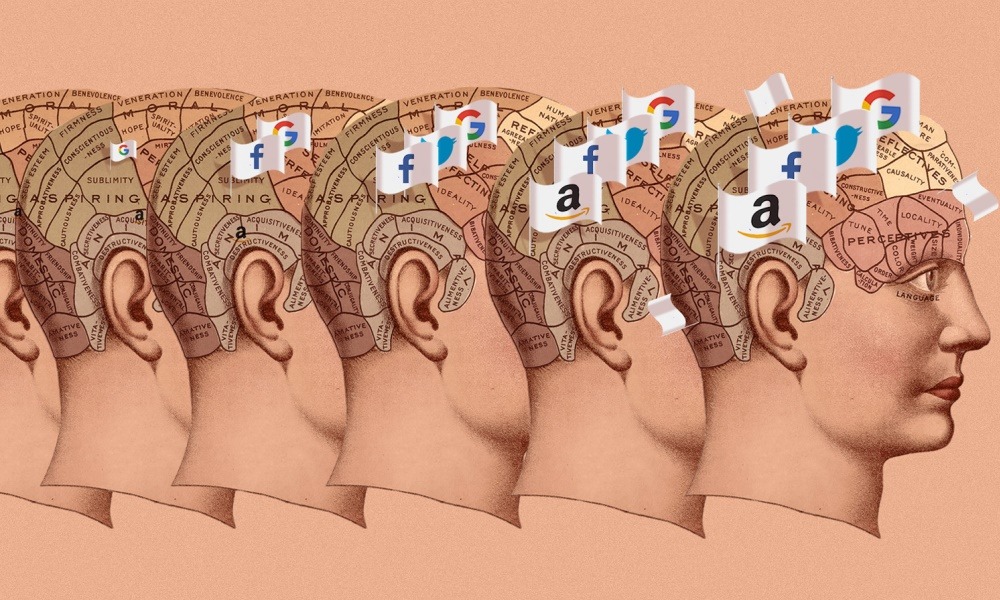

And this in turn brings us to an important question: what will come after Trump? Will America remain the same as it was 10-15 years ago? For if the boundaries of what is permissible have already expanded, who will move them back and when? Will this be done by the new elite — the “geniuses” of high-tech and Fintech? Will they actually want to spend their money, time and efforts to bring back the old times? Or will they be inclined to think that new times are coming when the world will be run by the creators and owners of artificial intelligence who dispose of an unbelievable quantity of information on people and their money and boast unimaginable opportunities to process such information, and certainly not “archaic” parliaments and the “antiquated” press? And will there be any need for law and order in its traditional form when information technologies can be used to directly control mass behaviour? Will the people holding themselves to be omnipotent actually perceive any need for checks and balances?

Incidentally, when present-day populist politicians like Donald Trump expand the boundaries of what is permissible in politics to fit their needs, objectively they also expand the boundaries for their opponents. And after Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential elections in 2020, it is highly unlikely that they will move these boundaries back voluntarily. No individual would voluntarily forego such opportunities — other than some maverick idealist, but this is highly unlikely. Society will also not demand any narrowing of the boundaries of what is permissible, as it is splintered and is no longer capable to engineer a hierarchy-based organisation of society’s proactive and engaged participants, because all their energy has been squandered online, freeing up in the process the offline space for asocial elements. Meanwhile senior management of modern businesses has no interest in any boundaries, because they are not run by individuals like Rockefeller or Morgan, but instead by people like Zuckerberg and Bezos who do not believe in checks and balances for politicians, and instead worship the magic of technologies and social engineering. Against this backdrop, the disintegration of the previous political system is likely to continue, regardless of the outcome of the US presidential elections in November 2020.

We have all the grounds for assuming that the world in actual fact will no longer resemble what it has been in the past. And this has nothing to do with the coronavirus epidemic.

First of all. Virtually everyone is forecasting a deceleration and in some important aspects a reversal of the global economic system as we know it, where the role of cross-border flows of products and resources increased, and that of national sovereignties weakened (See «The New Age economy»).

Such a reversal can be traced to factors existing long before the COVID-19 epidemic, the election of Trump, the migration crisis in Western Europe, Brexit and many other milestone events of the past five years. The age of global political supremacy of major multinationals hoped for by some, and feared by others did not happen.

The past six months not only failed to change the situation in this respect, but on the contrary promise to expedite a discernible trend.

In developed countries corrections to multinational supply chains have been encouraged — at the very least with the elimination of China, and at most with the maximum degree of localisation in one country or in a closed and limited group of countries. Additional steps are already being taken in respect of foreign investors and specialists in the USA and Japan. There is good reason to assume that the situation will continue developing in this vein.

Today, we can see forces proactively advocating for a decoupling of American (and in general Western) and Chinese business; for a return to the “sovereignisation” of trade and investment policies; for the de-offshorisation of national business and the return of business activity to “its own” jurisdictions. Naturally, this does not mean that insurmountable barriers will be erected to block goods and technologies, and that multinational ways of doing business will start to be scrapped. However, the growth rates of such processes, which tend to be called economic globalisation, will at the very least slow significantly. And this will happen now because any further advance of globalisation is impossible without some forms of supranational multilateral regulation at a time when the political influence of the proponents of such ideas is effectively on the wane everywhere.

At the same time, the greatest detachment will also clearly be manifested in politics. It is highly unlikely that the lower degree of coordination between Western countries is solely attributable to the personal qualities of the current generation of global leaders. The tensions between military and political allies patently disclose a growing deficit in mutual trust, and this is unlikely to be replaced by universal aspirations for unity, even if Donald Trump, Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron, Boris Johnson and Shinzo Abe were all to withdraw from the political stage. The lack of trust has deeper roots — based on the evolution of public opinion which has readily responded to populist and nationalist rhetoric.

This also renders impossible any so-called “new bipolarity” — the establishment in the world of two opposing camps united behind, accordingly, the USA and China. This confrontation does not represent a competition between two polar opposites, as was the case during the times of the USSR: today there is no fight between ideologies, and China has no areas of influence and allies (except for the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea). This is a fight for a change of leadership. The USA holds that China is seeking to take its place in global economic and over time technological rankings.

Therefore the picture emerging in reality is far more pluralistic and susceptible to change at any moment. And here COVID-19 has also fallen into line with this new reality: the reaction of governments to the pandemic and concomitant threats — both real and mythical — has objectively also distanced the world even more from a simple bipolar model.

Secondly. At the same time within each country the role of the state and government has increased perceptibly (in particular in Russia) albeit by virtue of the objective need to strengthen centralisation of management at a time of acute and clear threats to the health and lives of the population — even if the actual proportions and nature of this threat are not fully clear to everyone (and possibly, precisely for this reason). In this environment, the instinctive desire of the population to oppose the tightening of controls is also weakening for some time (See «On the political systems of the New Age»).

Naturally, all the so-called lockdowns which affected in general private, and not state business and social activity, were merely a temporary phenomenon and did not aspire to become part of some new normal. However, the information and communications sectors and services, to a large extent controlled by the authorities, have played a special role in the general direction of these changes. It is sufficient to say that the internet, which had appeared until comparatively recently to be a realm of unlimited individual freedom, has turned out to be a tool used to manipulate public consciousness, and is perhaps many more times powerful than the traditional printed mass media have ever been, deemed extremely vulnerable to administrative control. Moreover, thanks to the establishment of rules and preferences for certain participants in the information and communications sector, new tools of state supervision and control are becoming particularly effective (See «Information ochlocracy»).

To all intents and purposes, increasing economies of scale resulting from more extensive use of digital platforms will have even more material consequences — both when organising new forms of activity, and also controlling them. Today digital platforms for business and private communications have already ended up concentrated in the hands of a group of oligopolists of not only a national, but also a global order. This is a reference to mission-critical digital assets (in conjunction with capabilities and expertise) controlled by a limited number of people, businesses or countries. This may result, first and foremost, in a non-market, but political pricing tool and the lack of any objective oversight, and secondly, in digital inequality — fragmented and unequal access to mission-critical digital networks and technologies (both between countries and within them) as a result of unequal investment opportunities, a shortfall in the necessary professional qualifications, inadequate purchasing capacity or government restrictions.

Ensuring instant access to audiences of potential and actual consumers running into the millions, these platforms deliver immense gains to their owners and effectively block market competition mechanisms (in any case, in its usual forms and proportions). This complicates the access of new players to the market not only in these areas, but also in numerous adjoining sectors.

The situation is also exacerbated by the fact that big digital platforms are able not simply to provide infrastructure and technical services to their counterparties, but also to interact with them in this process, collect various information about them and to a large extent determine their future actions. While the collection of information on consumers and the programming of their consumption is by no means a new phenomenon, the staggering growth in the technical capabilities of these platforms to store and process mass data has turned them into powerful economic players.

Thirdly. Moreover, the financial, organisational and information opportunities of these information and communications super corporations potentially make them major political players. At the same time, their oligopolistic, and in certain segments virtual monopoly positions are becoming politically significant in terms of the potential consequences for society.

The influence of the coronavirus epidemic here also cannot be termed neutral. On the one hand, the pandemic enabled governments and the agents of the digital economy to increase the volumes of information being collected on the population, virtually unopposed, through the deployment of digital technologies in new areas and in new proportions, with this factor attributed to the measures required to understand the nature of the epidemic, curb the epidemic and implement subsequent preventive actions. On the other hand, the pandemic put on hold attempts to limit the monopolisation of this sector by the group of major players through administrative curbs and other forms of public intervention in their activities. It is undoubtedly the case that this will result in further concentration of information capabilities with a limited number of actors — selected private corporations, state departments and specific individuals — and this is all happening against the backdrop of the growing opacity of the terms and extent of the use of information technologies.

And even though fears that these player will receive unlimited economic and political power may appear exaggerated and excessive at this historical stage, the trend of such concentration exists and should be clearly understood, as should the resulting consequences for society.

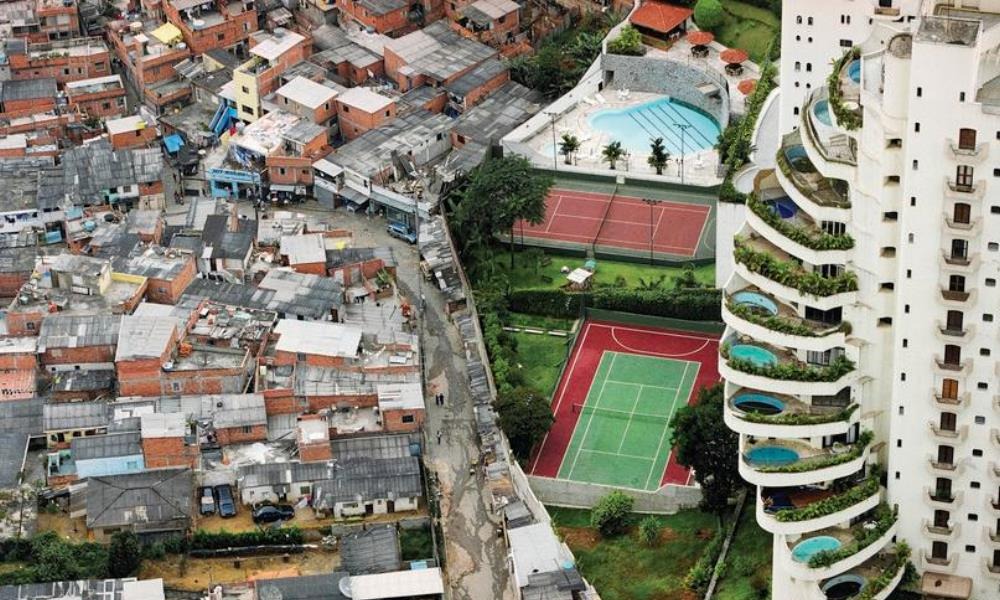

Fourthly. Analysing international experience of the past six months, the stratification of both the global community as a whole, and also individual national societies, has intensified perceptibly.

One aspect of this stratification, in both business and financially, is attributable to the impact of the pandemic on the global economy. This recession promises to be more profound and protracted than the so-called Great Recession — the financial and economic crisis of 2008-20091.

After a new strong push, the structural shift towards the online economy (which is, as noted earlier, intrinsically more concentrated and differentiated in terms of the size and stability of earnings) has also increased the inequality of individual opportunity. And this concerns not only the inequality of opportunities to derive income, but also importantly inequality in social and professional adaptation, in ensuring the stability of an individual’s position, protection from the adverse impact of the external environment, etc. And even though for the time being this does not involve the emergence of new closed castes, new social partitions, albeit informal, are still appearing in society.

Whereas the general trend at the end of the 20th century was to acknowledge various types of underprivileged segments and minorities and work out how to integrate them into a single society with common rules for everyone, in recent years a different process has been observed: there has been an increase in the popularity of ideas and practices indicative of social engineering — attempts to guarantee a stable environment for ruling elites through control of the behaviour of social groups as part of the hierarchical system. In other words, people have an opportunity to compete in society through the interaction of a large number of small groups consolidating over certain specific interests, at the same time as the objective of articulating common interests and introducing them into the collective consciousness is assumed by the self-appointed quasi elite with the assistance of the social engineers servicing them.

Fifth. This is in principle a different model of the political structure where the main components of the previous ideal model (political parties competing in elections, representing differing ideological concepts and interests of major groups; the establishment of power based on a balance of interests; the division of authoritative powers between different seats of power to prevent any potential usurpation of rights) perform secondary functions and no longer work in fundamentally important moments.

For the time being, the new system does not exist anywhere in its entirety and visibly. However, the contours of the system have already begun to take shape. The fight of governments against the coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the crisis phenomena in the previous political system, and we can expect to see in the coming years a number of stories on the transformation of politics.

We are witnessing before our very eyes a serious transformation of the information and communications space which has already led to notable political and social changes and may have even more significant consequences in the medium and long term.

Drawing on the example of the mass media, one can track the extent to which serious changes have happened over the past 50 years.

Firstly, the flow of information is now based on opinions and derivatives of such opinions, instead of actual events (the reactions of some people to the opinions of other people: “rejected”, “denounced”, “ridiculed”, etc.).

Secondly, the mass media reneged on the function of classifying and hierarchising reports which had been mandatory in the past (for the serious press). Now reports and opinions follow in a continuous stream, and no attempt is made to rank them in terms of significance and relevance.

Thirdly, “virality” has become the norm, when one comments snowballs into strings of dozens or even hundreds of other comments: comments on comments, comments on reactions to the comments, comments on reactions to reactions on the comments (and leading in the process to the flourishing of so-called news aggregators).

Fourthly, bias is perceived today as the desired norm. Any reports on facts without any interpretation don’t sell: it is the interpretation of reality that sells.

This results in a haphazard flow of information existing in parallel and almost independently of reality. Several flows mean several parallel realities, with each one literally created by the disseminators of the information. Meanwhile real life and its most important aspects (for example, the distribution of resources and their use) become non-public and leave (or are removed) from the focus of public attention.

This opens up extensive opportunities to manipulate the information agenda and in the process politics for the widescale redistribution of economic power, and going forward political power. Strictly speaking, this is already happening today: such “inventions” as social networks, cryptocurrencies, “green” business, etc., redistribute hundreds of billions of dollars between specific individuals.

The degree of concentration of ownership in the new economy (See “The New Age economy”) is by virtue of the technological specifics of the economy already higher than in the traditional industrial economy, while control of the information sector makes it possible to increase this concentration even more.

The immediate outcome is that traditional political competitive models in the new environment will undergo a profound crisis. Despite the material significance of “big money”, these models were still based on open and rational agenda and implied the responsibility of politicians before elites (the proverbial “upper classes”). Today everything is changing, has already changed to a large extent, but something else will also change: the key is that at present it is unclear how everything will play out in the near future. However, it is highly likely that any attempts to return to the past will fail.

At the same time, in actual fact the technical aspect of the transformation is being implemented in practice through a revolution in the technical and technological foundation of the information and communications space. These changes impact society, ways and opportunities to manage them, public institutions and even the values being upheld.

Naturally, human nature could not change in such a short period of time. However, the methods used to organise people and opportunities to affect society and the system of relationships changed beyond comparison in previous decades. The forms and methods used to organise public relations through information flows and communications channels not only impacted the intensity of these relations, but also the content that they generated, including the establishment of prevalent values in society. Above all, we have been observing this everywhere recently.

If we put to one side technical aspects, the key development and continuing change is the abrupt decrease in social and institutional barriers for access to the mass information business. Today, in order to publish and make accessible any information content to the broadest audience — reports on actual or imaginary events, and also discussions on practically any topic — there is no need for major financial investments, lobbying or the support of society (neither society as a whole or even individual segments).

Now this is accessible to virtually any individual, even someone with modest means or a minimum level of intellectual development, as demonstrated by the hundreds of millions of users who express their views on a regular basis on social networks and other online platforms.

Such democratisation of the information and communications space results brings it closer to the expression of spontaneous mass consciousness. As a rule, the new platforms and channels have no filters, and if there are any, then they are partly or fully circumvented by anyone interested in doing so.

The underlying causes can be found not only in the development of information technologies. Traditional mass media, political structures and politicians have been more than willing to adopt the ideas of the new media formats, and have used them to popularise and broadcast their views to the masses. In particular, the elites have toyed for a long time with populist slogans and promises. The problem is not only that politicians made promises, but did not keep them (like the promise of former British Prime Minister David Cameron to cut immigration). They fed populism and used it to attain their goals and win elections: Cameron himself exploited for a long time the promise to conduct a Brexit referendum as a populist lure for the electorate. At the time, this might have looked like the right move, “going with the flow” and testing out new trends. In the end, however, everything crystallised for Great Britain into a big and dangerous problem: the prospects of actually exiting the EU without any agreement on economic relations.

Owing to the lack of boundaries and filters, this inevitably results in the fact that qualitatively content reflecting the interests, preferences and perceptions of the biggest segment of the population and a corresponding conceptual framework is prioritised. It goes without saying that in principle such a phenomenon cannot be called new in history: to all intents and purposes, it does not differ in any way from the spontaneous exchange of information, rumours and fabrications in markets in mediaeval times or in public houses and taverns in subsequent centuries. However, the volume of flows of mass consciousness and possible outreach to an audience in the new formats exceeds corresponding parameters of their historical counterparts many times over, if not by an even greater magnitude.

A revolution of standards and goals has occurred in the information and communications space: concepts determined to some extent or other by the educated part of society have been replaced by perceptions of what is normal, fitting and admissible engendered spontaneously from below.

Another new phenomenon was the disappearance of the previous hierarchy of sources of information and judgments. The flip side of the widespread availability of information platforms was the fall in their public significance. Previous respect for the written word (to a large extent related to the number of print publications, which are incomparable with modern volumes of printed information) was replaced by remarkable shallowness on a par with everyday idle talk. Meanwhile the increase in the supply of studies and resulting decrease in the quality and significance of all forms of learning undermined trust in the actual institution of education as a source of qualified understanding and authoritative judgments, and put on the same level the words of the so-called educational classes and the opinion of the man on the street.

In the eyes of a rank-and-file user of new information and communications platforms, all opinions are equally meaningful, regardless of source, create the semblance of choice between them and may easily be rejected if the user disagrees with them. In other words, in the new system of coordinates the professional assessment of an expert who has dedicated his life to studying the specialist subject under discussion is worth almost as much as a banality repeated for the thousandth time by a dilettante or the judgmental retort of an illiterate anonymous troll on this topic.

The British sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman also noted several years ago: “Orthodox brainwashing was aimed at clearing the site of the relics of old logic and sense, so as to make it ready for the construction of new logic and sense. Present-day brainwashing is keeping the site permanently void and barren, admitting nothing more orderly than a haphazard scattering of tents as easy to erect as to dismantle. It is no longer a one-off purposeful undertaking, but a continuous action holding its own continuity to be its sole purpose.”1

At the same time, the spontaneity of the new information and communications environment does not imply a neutral attitude to the content being put out. Human consciousness is not a clean sheet of paper: perception of external signals is susceptible to the strongest impact of instincts, fears and prejudices. Some elements of the media space are instinctively rejected or called into question, others are accepted readily and even enthusiastically as they fit the matrix representing the world most comfortable for the consumer of the information. Naturally, the configuration of this matrix is not the same for everyone — there are numerous variations, cultural codes enshrined in education. However, the laws of large numbers make it possible to compile a picture of the most typical and effective combinations. This creates the premises for the effective manipulation of mass consciousness, the dissemination of preconceptions and opinions, and as a result management of social behaviour.

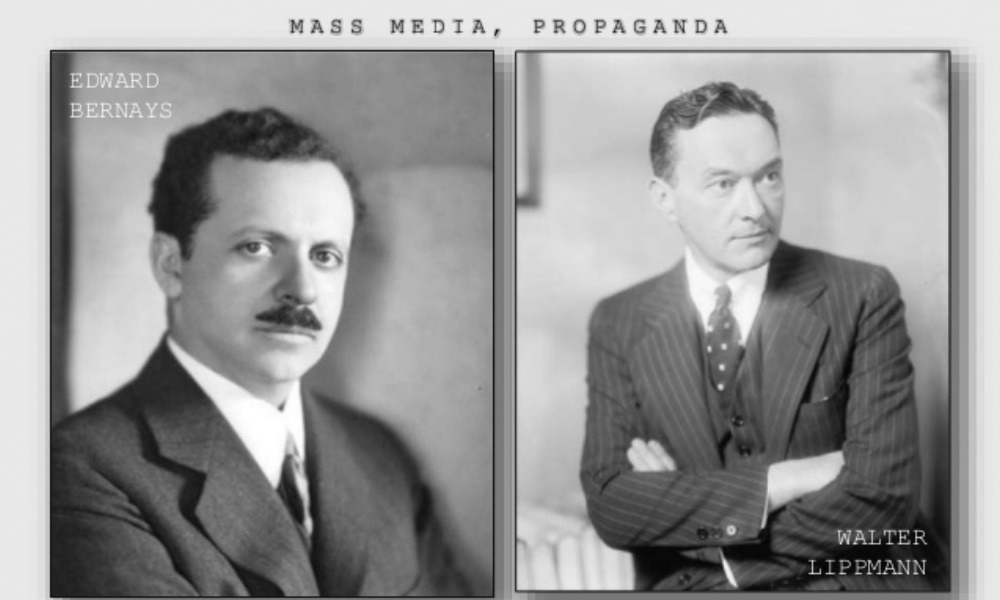

Approximately a hundred years ago this was noticed by observant experts. One only has to recall the Americans Edward Bernays and Walter Lippmann, the biggest public relations specialists in the 20th century2. “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society”, wrote Bernays in his work Propaganda3. Lippmann is primarily known in Russia for his concept of public opinion, which became a classic, and also for popularising the concept of a stereotype. Subsequently, these concepts were proactively used by advertisers and marketers, and then by politicians as well (albeit instinctively, without a theoretical base: it is highly likely that various rulers have used corresponding techniques at the very least for several hundred years). The specifics of the current stage are that the empirical experience tried and tested in advertising and political technologies can now be combined with vast network platforms, without any material financial costs, guaranteeing access to audiences running in the millions. And this is all happening against the backdrop of modern popular consciousness freed from the boundaries imposed on it by social hierarchies and the traditional mass media that they control.

Consequently, in the context of frequent crises and the psychological uncertainty of the masses, when confronted by various threats (military, political, economic, environmental, terrorist and other), which are proactively spread by an “extensive” information environment, factional groups with limited interests, who lack both political power and material economic resources, may have gained a chance for the first time in history to dispose of tools to manipulate the consciousness of millions of people and, accordingly, significant historical processes.

For the time being, nobody is ready to predict the consequences of such a revolution of opportunities — who will be able to leverage these tools to the full and how. Clearly, however, many people have motives for leveraging these new opportunities.

In the West this concerns first and foremost forces aggressively playing the card of boundless populism. Frequently, this happens in a combination with different extremist, fringe and sectarian forces interested in spreading their influence, but not disposing of major resources and the legitimacy required to act using conventional methods in legal public politics. In response, in public discourse pent-up demand for security is strengthening against a weakening desire for freedom (for example, the mass protests in the USA under the slogan of Black Lives Matter frequently accompanied by disorder and violence exacerbated this problem in American society). From the state’s perspective, sooner or later this translates into the tightening of regulation and controls. And these measures will find more and more public understanding, if not support. A tolerance of everyday restrictions and possible interference in private life has increased, inter alia, in the educated strata of society. It is highly likely that political restrictions will similarly be adopted without any major outcry.

Finally, solidarity in the upper tier of society has weakened. The elite is unable to consolidate in order to block politicians who are trying to take power, relying on the moods of the masses (the lowest common denominator), including an anti-establishment thrust. And this leads to a surge in populism. Why this happens is a different issue. However, the simple fact remains: the ability of the traditional elite to safeguard its role as the ruling class (“politically responsible class”) from different foreign elements (in ideological and cultural aspects) has weakened significantly.

Meanwhile everyone knows that as a matter of fact populism easily segues into fascism (scientifically, the ideology forming an authoritarian state, monopolisation in the economy and politics, assertions of a global mission). “We are the best because we have been told that we are the best” — that is how messages from on high are perceived by the people. And this leads to the “unity of the people and the powers-that-be”, and the fight against contrived imaginary external threats as the meaning of statehood, and the fight against betrayals and conspiracies within the country as the foundation of security, and the chain “people — party — leader” — in general, the full set of corresponding propositions. All this worked in the past and is working now, which means that it will also work in the future. And it is not at all essential that these processes assume explicit or grotesque forms: from the outside, the movement may be barely perceptible, frequently actually unperceivable. Furthermore, the façade may remain the same, notwithstanding changes to the content. In general, it can be assumed that the world, and the West in particular, already expects major shocks in the immediate future.

It is worth noting that when the system stopped delivering previous results, in the West people would blame cyberattacks and the interference of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, who were allegedly able at the drop of a hat to undermine democracy in Western countries (local activists against the “sabotage” of Eastern authoritarian regimes use this to remind our fellow citizens who are nostalgic for the USSR and are convinced that the Soviet Union was destroyed by foreign secret services). In the worst-case scenario, the actions of greedy bankers who forced the masses to pay for their financial losses from crises are cited as the reasons why liberal societies “have lost their legitimacy in the eyes of their citizens”, as a result the masses became aggrieved and voted for Trump and likeminded individuals.

It is true that populists and political opportunists existed in the past. As a rule, however, they were prevented from rising to the political Olympus by filters set in place by party systems and the “big press” owned by politically responsible businesses. In those conditions, the frustration that would intensify now and then in society did not reverse the Western political system.

So what is causing the deformation of former reliable political constructs in Western countries? Clearly, first and foremost the material and growing lag of the opportunities of modern man compared to the information and communications and digital technologies that he created over previous decades.

In particular, these are technological changes in the social and information environment, creating opportunities for politicians to recruit proponents, bypassing the “serious” mass media which have weakened considerably; uncontrolled primaries destroying the identity of political organisations; the opportunity to use political and social-psychological technologies to target audiences directly; the lifting of previous political and moral taboos, barriers based on traditions, different filters (including monetary ones) as a result of the totality of the use of the Internet with its impersonality and anonymity. And that leads to everything today called in the West the “crisis of liberal democracy” (See «On the political systems of the New Age»).

In Russia new platforms are also engendering different temptations for the most diverse interest groups. For example, in the case of the protest-minded public, this is expressed in a rejection of serious politics and a desire to develop civil activism and pseudo-political concepts in various forms of network space. However, the criticisms and protest moods that can be found on online platforms and on social networks, and even protest actions offline should not mislead anyone: in general, virtually the entire media space in Russia is controlled by structures linked to the powers-that-be and in the end meet the interests of the ruling regime. Admittedly, the latter circumstance is frequently masked by repressive measures against various platforms. As a result one may gain the impression that there is real confrontation between the authorities and certain representatives of Russia’s IT sector.

It is another matter that the heterogeneity of the ruling elite engenders constant friction within when different groupings “plant” information online in a bid to consolidate their positions. This can range from all manner of anti-establishment attacks and constructs — from moderate criticism of the regime to over-the-top assertions, exposures, insinuations about mythical conspiracies and the underhand practices of a “shadow executive” and “world governments”.

These days such attacks change little in the real world. However, this does not mean that this will always be the case. Similar to the destructive potential of weapons of mass destruction, at some stage their owners give in to soaring ambitions and unsubstantiated aspirations to exert global influence, as opportunities to effectively work with the collective consciousness will trigger the temptation to exploit these tools to implement various attempts at political coups for the redistribution of power and property.

Society is entering unchartered territory, and the most varied turns in events, including unpredictable developments, are possible. However, it is already clear today: the increasing information ochlocracy will not result in freedom for society, enable people to live their lives without fear or result in respect for the individual.

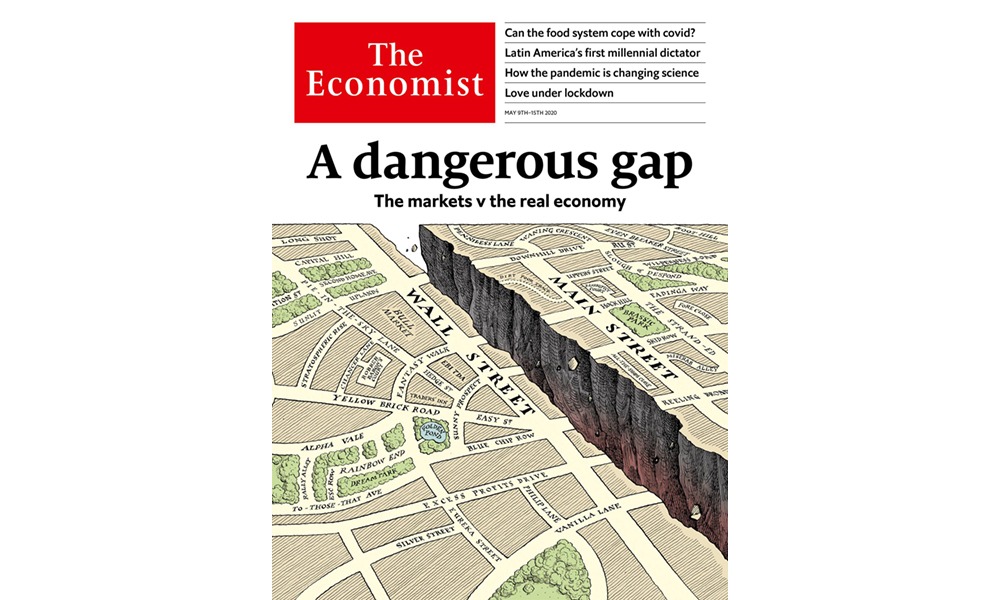

These days virtually all economic analysts concur that the pandemic and its consequences are exacerbating key negative trends in the global economy, such as the increasing gap between stock market indices and real economic processes, the rise in monopolies and growth of inequality. Arguably, the pandemic is consolidating the political power of oligarchic interests and postponing the opportunity to implement urgent economic reforms, creating an extremely conservative economic context (See «The pandemic and politics»).

When considering the link between the global financial and economic crisis of 2008-2009 and the current recession with long-term trends, fundamentally new factors were identified in the modern global economy1. For example, consolidation of the impact of historical and technological rents on structural changes in developed countries to the benefit of the new economy, and reinforcement of material inequality both within developed economies and also in the global economy, and also a change in the nature of the impact of scientific and technological progress on the economy. The thesis that public perceptions of benefits play a far bigger role in the economy than commonly believed has been confirmed.

Recent events have not only confirmed these observations, but have in many instances brought the consequences of these new phenomena in the economy to the foreground. Risks and fears related to the pandemic are expediting automation and use of robotics in many production facilities and services, notes the well-known American economist Joseph Stiglitz2. This also concerns sectors where nothing of the kind had happened in the past: education and health. The standard responses to such a challenge of accelerating professional retraining will be insufficient. Stiglitz holds: “There will need to be a comprehensive programme to reduce income inequality.” In his opinion, such a programme should proceed from recognition “that the competitive equilibrium model” that “has dominated economists’ thinking for more than a century” is already poorly suited to describe the modern economy with its monopoly controls on markets. Stiglitz notes: “Weakening constraints on corporate power; minimising the bargaining power of workers; and eroding rules governing the exploitation of consumers, borrowers, students, and workers have all worked together to create a poorer-performing economy marked by greater rent seeking and greater inequality.” He reminds us that the deterioration of the economy became apparent at the start of the pandemic when “American firms couldn’t even provide enough supplies of simple things like masks and gloves, let alone more complicated products like tests and ventilators.”

The situation in poorer countries is even worse, and affects directly both the American and the global economy. The economist is convinced: “The pandemic won’t be controlled until it is controlled everywhere, and the economic downturn won’t be tamed until there is a robust global recovery.” That is why it is in everyone’s interests to support countries falling behind in the fight against the pandemic, including the interests of rich countries.

To date, however, agreement has not even been reached on measures which had been implemented in the fight against the global financial crisis in 2009. This concerns the issue of special drawing rights by the IMF for USD 500 billion. Stiglitz believes that this has not happened due to resistance primarily from the USA and India. In addition, current “cheap money” will soon cause a wave of private and public debt crises and inevitable debt restructuring in some form or other.

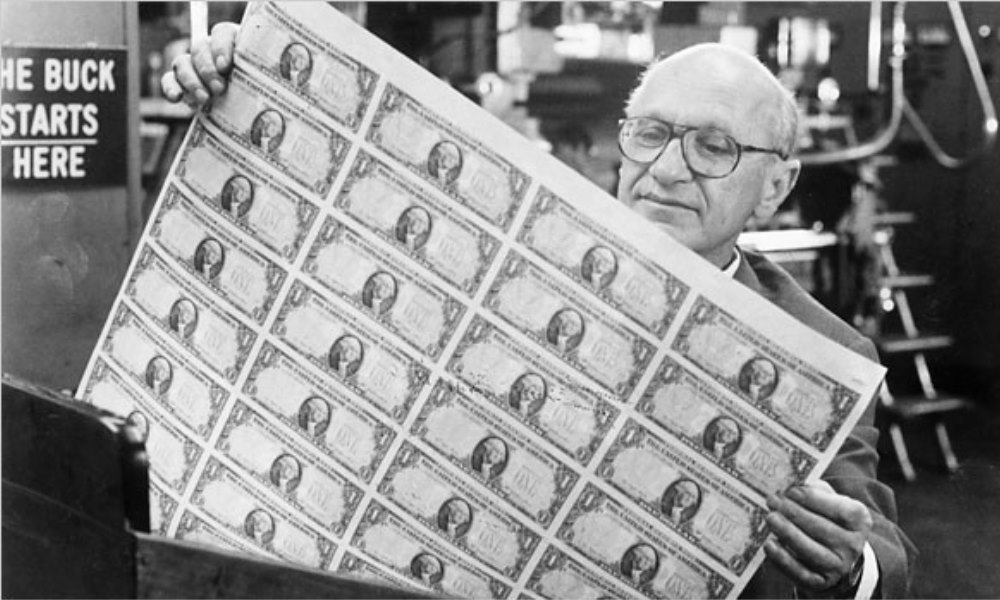

At the end of August the Chair of the Federal Reserve System Jeremy Powell declared an official change in the policy of the Federal Reserve System regarding inflation: instead of the objective of maintaining inflation at 2%, the so-called “targeting of inflation” has the goal of maintaining it on average at 2%. In other words, now a higher level of inflation is becoming in principle permissible, while the Federal Reserve System may hold the key rate at a level close to zero even if inflation rises above 2% for a “comparatively short” period of time. Against the backdrop of this news, the stock market shot up in delight. To all intents and purposes, this is a further development of the previous policy of pumping up the economy with “cheap money”. However, as Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist at banking institution and brokerage firm Charles Schwab, one of the large players on the stock market, explains, this money could not access the real economy, which was to a large extent in lockdown3. That is why all these funds went into the stock market and other exchanges, including trade in precious metals and junk bonds. The American financier Ray Dalio also writes about this trend, which appeared not only during the pandemic, but also during a decade of post-crisis “cheap money”4.

As a whole the stock market fully recovered after the March fall as if there had been no pandemic, and even went off the charts to pre-crisis levels (Dow Jones and S&P 500 have risen since March by 50%, while the NASDAQ-100, made up of the equity securities of digital and technology economy was up, 33%5).

However, the stock market is pulling away more and more from the economy, which is moving in the opposite direction. Real American GDP in the second quarter of 2020 contracted by 33%6. Recently four major retailers have filed for bankruptcy. At the same time, technology behemoths, such as Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Apple, Netflix, Facebook, did not suffer in the current situation, while some of them even benefited7. In particular, Amazon obtained one of the cheapest credit facilities in the entire history of the corporate securities market, while the net worth of its owner Jeff Bezos increased by USD 80 billion during the pandemic8.

The gap between stock market indices and the real economy is far from a paradox, writes Nobel Laureate and Professor of Economics Emeritus of Standard University Michael Spence9. In reality the stock market is reflecting “powerful underlying trends amplified by the “pandemic economy.” He notes: “Market valuations are increasingly based on intangible assets, not least the ownership and control of data …” According to one recent study of Standard & Poor’s 500, writes Spence: “stocks in companies with high levels of intangible capital per employee have recorded the biggest gains this year.” A detailed analysis of this trend in figures and graphs was published by Bloomberg Agency, under a typical heading which laid bare the ideological component of the new economy: “Stock Market Warns Workers That They’re the Problem for Business”10.

Spence also links this trend with the transition to digital technologies and partial closure of the most labour-intensive sectors, which has accelerated since the start of the pandemic (such as airline travel), where added value is generated thanks to labour and tangible capital. The Nobel laureate shares the opinion of Liz Ann Sonders that this is also facilitated by “cheap money”, reflecting government need to increase public debt in order to finance recovery programmes.

In general, it goes without saying that current developments in the global economic system are not only due to quarantines and lockdowns. A new era is coming which will clearly dovetail with the new economy. This is a wide-ranging topic. However, several concepts can be expressed briefly here.

The first concept is that the economy, as we all know, represents first and foremost the behaviour of economic agents. It is worth noting there that the psychology of economic agents is primary and unpredictable. The pretentious declarations of “true” economists that everything in the economy has been duly factored in and calculated, that they have “checked the harmony with algebra” and deduced clear formulae of the dependencies between all of them, are rarely confirmed in practice. Every time the reaction to economic variables may differ, and they cannot be predicted or calculated.

The second concept is that the world is entering a period of systemic change, including the economy (See «On the political systems of the New Age»). This is happening primarily because nobody knows where to invest and how exactly. Previously, this was more or less understandable, but isn’t now. And general phrases along the lines “the previous economy is being replaced by the new knowledge economy” fail to offer any clarity to the people who are required to adopt specific investment decisions.

In actual fact, this is not a “knowledge economy”, but instead a “post-knowledge economy” where every conceivable item of knowledge: а) May or may not be in demand; b) There are no mechanisms for consolidating specific knowledge as universally accepted (millions of “experts”, tens of thousands of theories and versions, thousands of communities — and they all say that they represent the supreme authority). This is particularly true in an environment where supply and demand depend not so much on technical decisions which make it possible to manufacture something that is clearly useful more rapidly, more cheaply and in large volumes (as was the case in the 19th century and throughout most of the 20th century), as on the manipulation of perceptions of our actual needs. In this scenario, needs simply cannot be calculated with a sufficient degree of probability. Naturally, the only exception would be instances when you yourself form the needs which are only being implemented for a select group, and definitely not for the masses.

That is why borrowing is now so cheap — however, nobody can take up the offer (if we rule out fraudsters).

This leads to a paradoxical situation: despite the abundance of “cheap money”, there is no quantitative growth, and resources are not growing more expensive. This can be observed most explicitly, for example, in Japan, but is not a purely Japanese phenomenon. In virtually all developed countries central banks are offering virtually free money in unprecedented proportions, while inflation remains at zero or at a very low level.

The fact is that money is not being handed out directly to consumers, but is being offered primarily as a loan to the financial sector. The funds accruing to consumers through the financing of budget deficits are to a large extent neutralised by the technology behemoths which are on the one hand digitising the services sector (including financial services), and thereby taking their rental income, and on the other hand absorbing additional liquidity through growth of their own capitalisation and the cryptocurrency product market.

Previously money assumed the role of the main limiting factor: if there were opportunities to take out big loans at low interest rates, then prudent companies would not find it hard to make profitable investments (despite the fact that mistakes would naturally happen, and the risks would be high and comparable with potential profits). Now, however, as a result of the expansion of information, communications and digital technologies, boundaries are determined by the ability to influence demand, form and attract this demand by persistently targeting the consciousness of consumers and managing them. And this is already a completely different economic system, a different system of business coordinates. And it goes without saying that there are different beneficiaries.

It would be wrong to say that there has been no discussion in Western political and economic research on the need to reform the existing system. The pandemic and the economic problems provoked or exacerbated by its impact, together with the threat of the authoritarian transformation of the political structure in the USA, are reviving this eternal discussion of ways to reform capitalism. Over the past few years the mainstream focus of the discussion was the microeconomics of big corporations. To a large extent, this was due to clear-cut or indirect acknowledgment that attempts by the authorities to materially reform capitalism through legislative institutions would effectively be blocked by big capital which wields control over these institutions through the financing system of election campaigns, the mass media and stock markets.

The main idea of the discussions during the past decade has been to change the goals of a company — to make the transition from maximising shareholder profits (an objective promoted by Milton Friedman11 and other representatives of the Chicago School of Economics) to achieving an optimal balance of the interests of different groups of people who affect the activities of a company directly or indirectly: shareholders, employees, suppliers, creditors, the consumers of their products and geographical neighbours. Harvard economist Dani Rodrik writes that the old microeconomic theory was based on assumptions regarding perfect competition on the market and the view that the availability of jobs is a purely economic factor12. In Rodrik’s opinion, both axioms became untenable after it became clear in economic and other social sciences that: 1) It is in principle impossible to dispose of infallible information when management and employees adopt economic decisions; 2) In the real economy “imperfect competition is the norm”; in other words, an unregulated market economy tends to end up with oligopolies or monopolies, consequently, companies enjoy power over employees that is at variance with the theory of a free market; 3) A job is not a purely economic category, but a “crucial part of an adult’s personal and social identity”, and the disappearance of jobs leads to destructive socio-political consequences for the middle class13.

As another Harvard scholar John Ruggie writes, the conceptual framework for this direction is the perception that through common efforts both from the outside and within it is possible to develop the social identity of a corporation, imbue major capitalists with specific behavioural norms, and educate them about their “core interests”, which coincide with the interests of employees and environmentalists, and thereby achieve the “self-regulation” of business14. Enthusiasm for these ideas is attributable to the fact that traditional forms of state and international regulation have fallen into decline and no longer work — due in no small part to the repudiation by democracy of political institutions which had ensured this external regulation (See «What should be done? Institutionalisation of values»).

However, recent research shows that the effectiveness of attempts at psycho-ideological transformation of the world of big capital and corporate management remains fairly low. For example, Harvard researchers Lucien Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita assert that the entire plan to reform corporate governance for its “socialisation” and market self-regulation is little more than a harmful illusion15. In the opinion of the researchers, this diverts the limited resources of a company and deflects discussion on the reforms of capitalism from the only effective area, namely the drafting of legislative and other political measures to curb capitalist excesses. At the same time, the authors acknowledge that movement along this path is extremely complicated, if not completely blocked16.

“There Is a Direct Line from Milton Friedmann to Trump’s Assault on Democracy” — this was the heading of a policy article that he published recently17. This direct line runs through a system where the “system for creating the rules of the game is corrupt”: as the advocates of market fundamentalism, representing the interests of big corporations, cannot impose their ideology on society in free elections, they do this through nationalism, racism and xenophobia18, which traditionally strikes a chord with the masses. What should be done? In Wolf’s opinion, corporations should be banned from participating in politics, inter alia, from financing election campaigns. He does not clarify who would be able to do this, given the degree of control of big business on politicians (something Wolf writes about).

Incidentally, Dani Rodrik might object here19 that the problem does not concern only financial control, but also the intellectual control of corporations, in other words, control over production processes and the dissemination of the information required to implement a competent economic policy, including business regulation. This intellectual control enables corporations to control the way problems may be articulated and filter any proposed solutions.

However, this is particularly interesting. The economic mainstream (with its beloved regressions and pretensions at profundity) has nothing to say about the appearance of some new global economic system. The most recent example is a global research report from Deutsche Bank20. The analytical department of Germany’s biggest financial institution is a completely representative forecasting structure with skilled personnel, graduates of the world’s best universities, and corresponding budgets. The research lists eight key “themes that will define the age of disorder”. Here you can find everything that you would expect to see: both global “concerns” about climate change, and “helicopter money”, with the “probability” of inflation, and new dynamism with the probability of inflation, and the impact of integration with the probability of fragmentation. And as a matter fact not a single word is written on what is happening in reality. Not a single word on why the previous levers of anti-cyclical regulation no longer work as they did in the past; why changes are being made to the structure and dynamics of demand and business capitalisation and what these changes are; how and why the nature and sources of economic and political power change, and who will now determine the political agenda.

It is true that the new economy will not expand instantaneously and the traditional real sector will recover partly after victory over the pandemic. However, the new global economic system, with the increasing concentration of information and digital assets at the very top of the economic pyramid will expand, and the disparity (and possibly, the conflict) between the two economies will become an intrinsic phenomenon in the medium and long term.

In current realities new technologies are becoming not only a way of organising mass protests, but also the trigger of the protests themselves.

For example, racial inequality inherent in the state, law enforcement and social system has been called the motive for the most recent protests in the USA. However, the actual causes of the protests both in America and also globally are far more complex and more profound. This concerns a far wider problem — the growing realisation of a social dead end — “the loss of any real future”, in other words, the underlying cause, for example, of the “Arab spring” in the Middle East, mass migration which has overwhelmed Europe, the yellow vests movement in France and many other appreciable social manifestations in the world over the past ten years1.