|

Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. Originally published

in The New York Review of Books, March 8, 2001

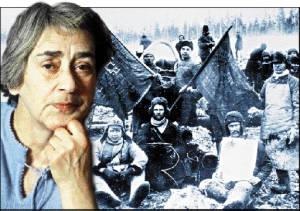

Elena Bonner, widow of the dissident Andrei Sakharov, says repression is creeping back

Soviet shadows : Elena Bonner, above, who grew up

under Stalin

and saw her mother sent to a labour camp,

believes

Russia is still tainted by totalitarianism

I was educated in Soviet schools, where courses in the history of the Communist party were obligatory. Later at medical school I studied philosophy (naturally Marxist-Leninist) and political economy. I did not ask myself whether there was so much as a grain of truth in them. Once I passed the exams, without which I could not graduate and become a doctor, I forgot everything I'd learnt. I had become a person without an intelligible view of the world.

My generation lived and grew up in an atmosphere of total fear, often without realising it. There were 23 pupils in my class, and 11 had parents who had been arrested.

Stalin's death and the fall of totalitarianism did not lead to the disappearance of this fear. It seemed to become part of our genetic structure, passed on to subsequent generations. I am not speaking of state ideology - we don't have one now and we don't need one - but of the absence of moral criteria and the ability to distinguish truth from lies, good from evil.

Today total state terror seems impossible, but we lived, and continue to live, in a state of lies. The great lie calls Russia a democratic state. The barely created election procedures were violated during the elections in Chechnya, which took place during the first Chechen war, and again in Yeltsin's 1996 election victory - which was decided largely by money and not the will of the voters. Then came the appointment of Putin as Yeltsin's heir, as if Russia were a monarchy.

The vertical regime constructed by President Putin - dividing Russia into okrugs, headed by presidential appointees, standardising the constitutions of the national republics, changing the way the upper house of the federal assembly is formed and limiting its functions - is presented as a way to bring order to the Russian state. But these transformations are turning multinational Russia from a federal state into a strictly centralised and unified one.

Putin: what democracy?

At the same time, people from the security establishment - the KGB-FSB and the army - are being appointed to top government posts, reinforcing their influence on the entire life of the country. There have also been a series of arrests and court trials - among them the case of the American businessman Edmond Pope and that of the navy captain Alexander Nikitin, who were both accused of spying - that smack of lawlessness. And yet not a single political murder of recent

years (and there have been more than a few) has been completely resolved.

Another dangerous phenomenon, permeated with lies, is the expansion of state control over the media, under the cover of punishing financial violations and fighting corruption. While the state is destroying some holding companies and trusts that managed publications and television stations, it is creating, under its own control, others more powerful and even more corrupt.

The world knows about the government's attempts to take over national television, but few people have heard about what is happening to the media in outlying regions of the country, where similar attempts have often ended in violence. It looks as though in a short time there will be no truly free and independent television stations or other mass media in Russia.

But the greatest disaster and shame of the new Russia are the two Chechen wars and the genocide of the Chechen people. The wars were preceded by widespread anti-Chechen propaganda and lies. After many years of use in the Soviet Union and Russia of chuchmek, a derogatory term for all non-Slavic people, a new ethnic label came into being: "person of Caucasian nationality", used not only in the streets by the "masses", but in official documents.

I realise that I am speaking dangerous words. But the war has taken the lives of more than 100,000 civilians, Russian soldiers and Chechen fighters. It is impossible not to mention the bloody bombings and continuing killings of Chechens, as well as the detention camps, the uncounted dead children, women and old people, the thousands of refugees dying of cold and starvation under open skies and in tents. If this is not genocide, then what is it? With these two wars Russia has lost its newborn

democracy.

It is intolerable how many lies and falsehoods have been poured into the minds of people during these wars. The same goes for industrial and other catastrophes (the nuclear reactor explosion at Chernobyl, the earthquake at Neftegorsk, the loss of the Kursk submarine).

At the same time we continually hear official lies in Russian daily life, reminiscent of the lies in the Soviet Union. The truth can hardly stand up to the impact of so many lies. A young man once said to me of the Prague Spring: "That was when the Czechs attacked us."

Brought up on lies, a society cannot mature. It is an adolescent society, with all the characteristics of adolescence portrayed by William Golding in Lord of the Flies: needing a leader and his imitators, being aggressive and quick to take offence, simultaneously lying and trusting.

Those who sensed the falseness of Soviet society intuitively fled the lies of the humanities and took up concrete professions, becoming engineers, doctors, musicians. When it became possible, many emigrated. My mother, a party worker, went back to study architecture in 1933. It did not save her from the terror. Arrested in 1937, she designed barracks for prisoners and then, with her camp inmates, she built them.

With the fall of the totalitarian regime - with Stalin's death, Khrushchev's speech and the emergence of the liberals of the 1960s - came the era of the dissidents. Among them were disproportionately large numbers of physicists, mathematicians, engineers and biologists, and almost no historians or philosophers. But the dissidents were only a a few hundred people in a country that then extended over one sixth of the planet.

But the clarity of their vision gave them the strength to reject lies and preserved their self-respect without which there is no respect for others and for life in general. Why do so few people have it? People speak of conscience. But it seems that conscience is the supreme existential value for only a very few people and, as we see from history, it is easily shrugged off.

In the preamble to his draft for a Soviet constitution, Andrei Sakharov wrote: "The goal of the peoples of the USSR and its government is a happy life, full of meaning, material and spiritual freedom, well-being and peace."

I do not know the goals of Russia's government today. But in the decades after Sakharov, Russia's people have not increased their happiness, even though he did everything humanly possible to put the country on the path leading to that goal.

This is an edited version of a speech given at the Hannah Arendt awards in Germany.

Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. Originally published in The New York Review of Books, March 8, 2001

© New York Review of Books 2001

See also:

To the original at The Sunday Times

The remains of Totalitarianism > Elena Bonner's speech (Part 2)

Elena Bonner's speech (Part 3) >

Elena Bonner's speech (Part 4)

Elena Bonner's speech (Part 5) > Elena Bonner's speech (Part 6)

|